Cooking with Ghosts

A Story of Wild Vinegar, Grief, and Home

This is the free version of my newsletter. If you want to support my writing, please consider a paid subscription for yourself or a gift subscription for a friend.

You can also support my work on Patreon, starting at $1/month.

If you can't afford the paid newsletter, but it would be an asset to you in your own culinary/writing/creative journey, please reach out and we'll figure something out!

A note:

This essay engages with the loss of multiple friends and family over a short period, and all that comes with that experience. Please be mindful that the grief process, in all its difficulty, is described in some depth here.

Some of my readers may also know the people I mention in this piece (Margaret, Jean, Justin, and Doc), so please be gentle on yourself as you read, if you decide to do so.

I've been sitting on this essay for years. Since 2018, to be exact.

Not because the sting of it is particularly sharp any more, now that the urns of ashes and files of estate paperwork have been closed or perhaps scattered to the wind.

But because it's something that feels both so intuitive, so basic, so much like an essay many people have written before, but yet something altogether new.

2018 marked the year when I explicitly began to view microbes as collaborators, as ever-present friends who helped me navigate my grief and to reconnect with my joy. I owe fermentation a lot, but one thing I owe this craft is helping point me towards my true north at a time I felt adrift at sea, battered by waves of fresh grief on one hand and the constantly-changing weather of caregiving on another.

For a long time, it was hard to imagine capturing that all-encompassing, transformative feeling of traumatic loss, undergirded by uplifting waves of possibility and creation. While our writing moves in shapes and sounds, what sound do you make that undulates with potential and loss? What is the shape of that kind of grief?

So I've sat on this essay, since I first wrote it in fits and starts at the deathbeds of loved ones, and in my own solitude after, then again in fits and starts later.

It's a grief I sometimes feel I've just awoken from, but mostly it's a grief I acknowledge as a turning point and like all turning points, one that encompasses the breadth of human experience and emotion. Joy and sorrow, loss and gratitude. The pain of missing and the joy of remembering.

Recently, my friend and fellow writer Kimberly Coburn used our conversations about grief and fermentation to write her own beautiful, moving piece about my experience using fermentation to heal from loss.

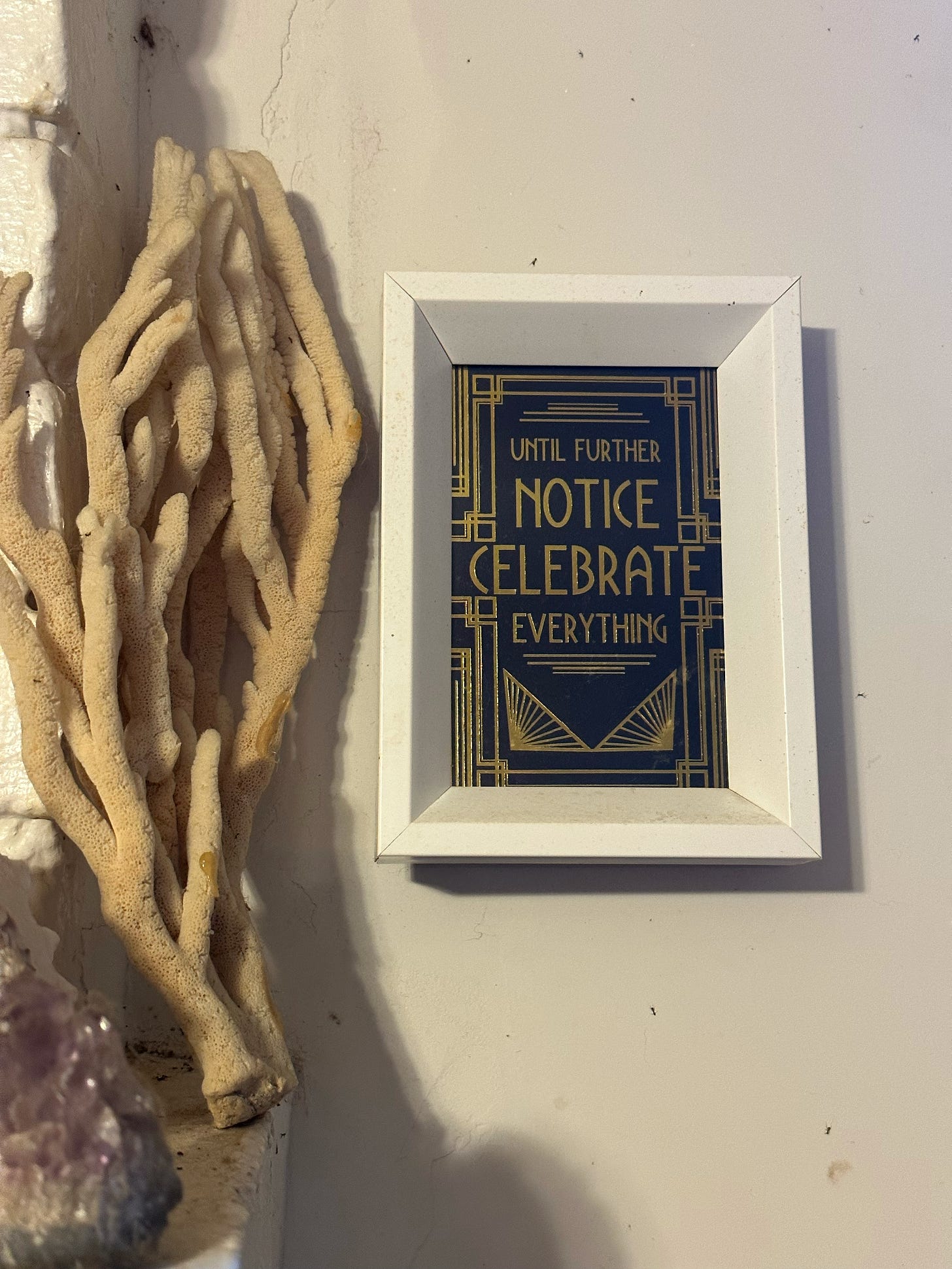

She titled the piece after a sign my grandma had hanging in her hallway that summarizes her ethos better than I ever could. It reads simply, "until further notice, celebrate everything."

I still feel like this essay is a work in progress, but perhaps that is the lesson of writing about grief: We can accept it is a space of transformation, but recognize that transformation is not necessarily transmutation. The grief may change, and may even eventually turn into something expansive and a touchstone for change, as it has for me, but it doesn't just disappear or change entirely.

My grief will always be here, but shaped differently, smaller, more familiar, more like an old friend and teacher (even if a melancholy one) than a sharp pain or a gaping black hole.

And it's a friend that helped to shape my relationship to food, and my experience as a cook.

Ultimately, that shaping has been hopeful, helpful, and has been transformative for me in its own right, just as my grief itself has transformed, and as both have transformed alongside the wild vinegars that got me through that journey.

So here's the essay, work in progress or otherwise, for you, to read alone or alongside Kimberly's writing.

One thing you notice sitting at someone's deathbed is the way it bends time.

Everything is set to a different clock: One of medications, eating, evacuating and, especially, sleeping. You'd think that when you care for someone who's sleeping most of the time, you'd sleep too, or be able to work, or do anything besides keep one ear out for them, ready to leap up and to feed or clean up, to bring over the little sectional container of pills organized by day and time. To be present.

You're always present even when you aren't in the same room, during these moments. When my grandma slept, I sat in the next room just beyond her bedroom door, writing the index to my book on afternoon tea. When my mom slept six months earlier, I sat by her bedside and scribbled out ideas for newsletter issues and classes, trying to maintain the rhythm of the business I had just founded a few weeks before she went into the hospital for the final time.

Not long before she came home on hospice and I scrambled to pack up my bags and join her.

Grief bends time, too: Time dilated, and stood still, when Doc and Justin died. Sudden, unexpected deaths, interwoven into a fabric of those long-lasting months of care, of illness, of waiting.

These sudden deaths spike up through the weave of that melancholy fabric like thorns from a rosebush caught in the shirt of an unwitting passerby. Even though Doc's death took place well after the others, grief changes the shape of time, and in this case, it felt almost like an ouroboros: A dark, difficult feeling I had just started to escape, only to be pulled back in by the new loss. A snake eating its own tail.

It was through all of this that I dove deep into my fermentation practice, that by creating I recentered myself. That by keeping parts of the people I love alive, through memory and through the act of co-creation and of sharing, that snake was unwound, the clock went back to as "usual" a pace as something as something as subjective as time can be.

That I was able to come back down to earth, and back home to myself.

Wild vinegar, grief, and home

Grandma died on Thanksgiving, mom a month before my birthday. When I called grandma to give her the news, the breaking I heard in her voice hurt just about as much as the fact that my mom was being wheeled out of the room next to me.

It came as no surprise, then, that grandma entered hospice not long after: Both of her children had passed, as had her husband. She was blessed with an incredible group of friends (as evidenced by the care they showed her at the end of her life), but she was also tired. I can't say I blame her.

As she entered her final months of life, I would do one week on and one week off at her house: Her friends, amazing nurses who coordinated so much of her care and who kept her comfortable and fed were an utter lifesaver.

At many moments through those months, I felt like I was barely holding it together. I have a vague memory of telling a friend, when asked how I was doing, that I felt like I was walking through pudding. Accurate, but absurd. But then little about grieving feels like it makes sense at the time.

A month or so before grandma passed, my friend Justin passed unexpectedly. A dear part of our friend group, someone who had made me belly laugh and mentored me professionally, gone in the blink of an eye. I felt the floor drop out from under me: the sludge I was wading through was up around my shoulders, yet I couldn't let myself sink because my grandma needed me.

When she passed, the urge to let that grief envelope me was enormous: I had barely begun unpacking one loss, how am I suddenly supposed to unpack three?

The thing that kept me sane was vinegar.

Vinegar making is a multi-step process that allows us to witness transformation in several ways: starting with raw ingredients, which transform to alcohol, and finally into vinegar.

Watching transformation on a microbial scale is a reminder that change is universal, and watching that transformation result in something beautiful and delicious is a hopeful reminder that even massive, world-upending shifts can bring positive outcomes.

On my last visit with grandma, she asked for her apple salad, a simple mayonnaise-based salad with diced apples and walnuts.

As I peeled the apples, I tucked their peels and cores into a jar, adding sugar and water to begin the process of fermenting them. I did it almost absentmindedly: As though an unseen force took over and guided me. I had no reason why I had to make vinegar, right there and right then, I just did, and ever since every time I hear that pull I listen. When she passed, the little jar and I started to make our way back home, the jar bubbling away as we went.

When I got there, I opened the lid, and the smell of the vinegar instantly transported me to her kitchen, and of good memories that helped to displace the sharp pang of loss.

Around the same time as grandma's death was Justin's funeral, during which a friend dug up the last carrots Justin grew, handing them to me.

I cradled the carrots throughout the funeral, handing out bits of carrot tops as a snack to interested fellow mourners. I'd say this is an uncommon occurrence, but it's actually pretty standard behavior for me at any social gathering. What was less common though, was the task of trying to turn those carrots and tops into as many foods as possible to share with friends: A way for us to collectively remember through digestion and reflection.

The carrots themselves became pickles, the tops turned into vinegar. Just as I had with the apples from grandma's house, I opted for a wild fermented vinegar, allowing the microbes from the soil tended by my friend's hands to transform our food into something that could nourish the people he left behind.

Both jars smelled like the places Justin and grandma both lived: In a very real way, it felt like I was carrying on her memory through the living food I made during our last week together. And in keeping a piece of her alive through food, I felt like I had a safe space in which to process my grief: One that acknowledged the loss, but acknowledged the hopefulness and healing that comes with connecting with the good memories of lost loved ones. Making and tending to the vinegar helped me realize that even in the depths of grief, we can create something beautiful and made with love.

Microbial landscapes shift just as our visible landscapes do: the makeup of a jar of sauerkraut, for example, changes depending on how long it's sat and what it's interacted with. I often viewed grief as a shifting landscape during this time, initially treacherous, eventually flattening out to undulating hills. Microbial and emotional reminders, alongside our visible and physical ones, that change is the only constant.

My vinegars changed, too: Over time, I've continued to replenish the vinegar with new apple scraps and carrot tops, and they have started to smell a bit less like my loved ones' spaces and a bit more like mine: a representation, of sorts, of my own return to self and healing.

When you don't have vinegar, use paint

Mom died before anyone else in this story, a traumatic experience in itself but also one that, by its arrangement, didn't leave me space to cook for mom or really share the quiet end of life moments with her she or I would have liked.

With grandma and Justin, I had ingredients I could take to make my ferments.

Even though the thought had not occurred to me at mom's house, perhaps part of the reason was because there simply was nothing available: Mom had been sick for months, and anything cooked in her kitchen was by one of her very kind home health aids, though her husband may have wandered into the kitchen occasionally. But there wasn't anything I could cook that had a trace of her: So instead of making my wild vinegar, I made art.

While the medium is different, the message remains the same: Using what we have to craft memory, and reminding ourselves that this crafting is an active process rather than a passive one. By making vinegar, I am choosing to remember and honor my friends and family in a certain way. By making art, I am doing the same.

Cooking with ghosts

Two years later, I stood in my kitchen, bottle of wine in hand, staring blankly into the middle distance, though technically, I suppose, staring at the half-finished meal I was supposed to be cooking for myself and my best friend, Doc.

Doc and I hadn't seen each other for probably two years at this point. Since not long after mom, grandma, and Justin had died. We made plans, though, and their triumphant return to Atlanta was to be marked by a feast: A meal to coincide with their arrival in town just before Thanksgiving.

I have complicated feelings about Thanksgiving, particularly with the history it represents, but I also know it is one of the few times friends are available and in town for things like a Friendsgiving celebration. So Friendsgiving has replaced Thanksgiving each year. This year, it was going to be small, just Doc and I, as everyone else was out of town or locked down on account of the pandemic.

We didn't really have a menu, I just got some autumnal ingredients and, figuring both of us cook things for a living, we would make it work, we thought we'd just mash them together as we felt called the day of.

But they passed the day before they were set to leave, two years to the day after grandma had.

It was a day of calling and breaking the news to friends, of tears. So many tears. Welling up from the depths of my soul, releasing both the relief that their experience was quick and the devastation that I didn't get to say goodbye.

Rather than spending Thanksgiving with my best friend as planned, I spent it by myself.

But I still cooked dinner, and when I did, it felt like Doc’s ghost was there beside me: I recalled lessons from our days working in the kitchen and conversations about food that spanned years. By the time I sat down to eat, I was still alone, but no longer lonely, and preparing some beloved dishes as Doc planned to gave me some comfort and needed closure.

This time, I didn't have a fresh ingredient they had held not long before their passing.

Nonetheless, I turned again to my now-familiar practice, taking the bits and bobs from my meal and transforming them into vinegar, and pickles, and whatever else. This time, though, there was a shift: while I expected to feel overwhelmed by the loneliness, instead my fermentation practice offered me hope.

Standing alone in my kitchen, staring at the jars in front of me, I was reminded of the collaborative nature of everything: These jars, the vegetables inside them, the microbes, the lids, the shelf they sat on, each brought to me through multiple transformations by many beings and many hands. Maybe Doc wasn't here, but if we're all the product of, and in the process of, constant collaboration, perhaps they still were, just transformed.

I was suddenly reminded a collaboration done years ago, touched by multiple hands: Mine, Doc's, and our friend Jeremy's. In the back of my fridge sat a jar of green birdseye chili hot sauce, with ginger and garlic. It's never been heated, which means to some extent or another its microbial life is still intact.

It's a reminder that, on the physical plane as much as anything else, we don't just disappear once we're gone. We linger, traces of our microbiome and hair and whatever else whispering through the places we've once been.

And sometimes, even in hot sauce, or vinegar, where our presence might linger for years, slowly transformed with each new making, just as it would have been if we were still here. Just as our grief is when the people we love are gone.

To Read:

Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen by Rebecca May Johnson

My copy of Small Fires accompanied me on my springtime travels to the UK and Ireland, emerging from the experience covered in marginalia, passages underlined and, most tellingly, passages with hearts, stars, or exclamation marks next to them.

The writing of this book is incredible: The way the narrative flows, the way we're moved from object to process to the food itself, and back again, left me surprised in the best ways and hungry for me. It's the kind of writing you read and say, "wow I wish I had written that," both for Johnson's insights about a life in food, drawing on both the personal and the historical, and for the tone of the writing itself.

When I talked about recipes last month (and here, and here), I talked about my personal experience with recipe writing, the history of recipe writing, how the form changes as time changes and how we actively influence form and function through our praxis.

Johnson talks about how the recipe changes her, noting that she moves between recipe as template and recipe as exact instructions, noting the changes in the experience with each making:

"My body is changed by the recipe -

after tasting it, I see flavour differently, which means I see things differently, because flavour is a quality of things, or can be."

The narration is half poetry, half prose, and while I think this form could be one that might lose some readers if not executed with great care, Johnson's writing remains accessible, engaging. I get the clear sense that every word that was put on the page was put down with great intention, which makes it all the more joy to read.

You can find Johnson's book here and follow her on Instagram here.

News:

If you’ve ordered my pickling starter blend with Burlap & Barrel, I’d love to hear how you like it!

The blend can be used for many things beyond pickles (though of course, it’s perfect there too). Here are some recipes to help spark your imagination:

Tea-poached salmon, buttermilk chicken breasts, sweet apple giardiniara, and of course, refrigerator pickles.

I've even used it to make mulled wine + cocktails before but note, the hot pepper definitely comes out with the warm wine, so easy does it!

To Make:

Grief pickles (Or joy pickles, or whatever you want these pickles to be)

As I wrote this essay, I thought about Kristen Iskandrian's essay "Grief Pickles" in Eat Joy, edited by Natalie Eve Garrett. Iskandrian's writing reflects the urgency we feel to do something, perhaps to short-circuit the feelings of helplessness and overwhelm and maybe even to help us find a way forward as we grope in the dark.

Iskandrian's pickles were, in essence, those vegetables in the fridge, tossed in brine, and Iskandrian had a similar experience to mine: Rather than pulling one back into the throes of grief, “we ate the alone-food together and felt, I think, less alone. Sometimes you have to celebrate sadness, too.”

Like Iskandrian, I find quick pickles a simple way to busy my hands in moments where I feel stuck, like I'm buzzing with energy from either an upsetting event or a joyful one, and need to move my hands to quiet my mind.

The key to making pickles in these moments is not to overthink it: Whatever vegetable or fruit you pull out of the crisper will probably be fine, I promise (maybe not lettuce. But maybe. Why not try it and see?)

The ratio I use for most of my standard pickle brines is one I learned from the 100+ year old pickled okra recipe shared with me by a best friend, and this brine hasn't failed me yet.

I sometimes tweak it based on what I'm making but remember, we're in a pickle emergency here, we can always tweak things for our later, calmer batches.

My brine ratio is: 8 parts water, 8 parts vinegar (ACV, rice wine, or distilled are my usual suspects, but use what you've got), and one part salt (I use sea salt, again, use what you have on hand).

So that would be 8 cups water, 8 cups vinegar, and 1 cup salt.

You probably aren't looking to make an industrial-sized batch of pickles (or maybe you are?) so to make one pint, those measurements translate to:

1 cup water, 1 cup salt, 2 tbsp salt.

Mix up your brine until your salt is dissolved, pour it over whatever vegetables you've chopped or sliced, close the lid, and stick the whole thing in the fridge overnight.

Open, enjoy, and feel your feelings (and celebrate them, perhaps with a friend as Iskandrian did). There will always be more pickles, and more things to celebrate (or grieve), so the time to celebrate the ones we have is now.

Supporting this newsletter literally makes my dreams come true, helping me devote my time to writing and to sending more and better recipes, interviews, and food stories to you. Thank you for being a part of my work!

This is so, so beautiful, Julia. Always in awe of the way you look at the world. So much love to you.

❤️❤️❤️