What's Old is New Again

Recipe Writing, and Use, as a Subjective Art

This is the free version of my newsletter. If you want to support my writing, please consider a paid subscription for yourself or a gift subscription for a friend.

You can also support my work on Patreon, starting at $1/month.

If you can't afford the paid newsletter, but it would be an asset to you in your own culinary/writing/creative journey, please reach out and we'll figure something out!

Sometimes I marvel at the ways history can come full circle, or more accurately, how we tend to return to traditions of 2-3 generations before us, but with each iteration the way we see those traditions changes, as they're viewed through the lens of a given place and time.

I can a ton of food every summer, just as I'm sure ancestors of mine generations ago did, but I do so on an electric stove. This means my practice and perspective are informed by the act of using that appliance:

My experience of turning a knob to produce heat, rather than loading up a woodfire or coal stove, means canning for me has a level of convenience, and the potential for spontaneity, offered by the fewer steps and instant heat source.

While my canning practice and my ancestors' may not look quite the same, we are approaching the way we cook with an eye towards similar outcomes or experiences (in this case, preserving food for later).

My cooking practice overall, and even my food preserving practices, rely on a hefty dose of intuition (within certain parameters, of course). In this practice, recipes serve as a source of inspiration, a practice I see reflected in the cookbooks and recipe cards passed down in my family: ingredients crossed out, replaced, highlighted.

Traces of use, in the form of stains, fingerprints, and faded ink, tell this story in an unwritten way as well: Whispering "this recipe was one of her favorites," or "see that thumbprint on the corner? She always held this card up by the edge while reading it." These traces breathe a bit of humanity, and a bit of their intuition, back into the room each time I read them.

That home cooking (intuitively or otherwise), was and often still is treated as "women's work" brings another layer to this as well. Passing on knowledge of how one cooks (not just how to cook generally), becomes an act of empowerment.

The home kitchen offers a potential site for sharing traditions and intuition: As much an act of breaking the rules as following them. It offers the opportunity to act outside of a strict set of rules, outside of the imposed external forces that exist in so many spaces in women's lives, in the past and today.

I know many people who have zero interest in learning family culinary practices, particularly friends who didn't consider their family members to be "good cooks." I can't speak to whether or not I'd love the flavor of their relatives' food, but to pass up the chance to try to understand that person's kitchen perspective boggles my mind.

To learn about how others cook for and feed us, however that looks, is possibly to be inspired, and at the very least an honor to the time they spent trying to keep us alive and full.

Who is a good cook?

Our ability to "be good cooks," a subjective phrase in itself, is often ascribed to being "skilled" in the kitchen, and certainly skill is involved. But, thinking just in terms of skill risks reducing "good cooking" to an externalized, strict way of viewing the world as input/output: Skills go in, good food comes out.

Many good cooks follow recipes that help them make wonderful meals and feed the ones they love. I love recipes, and I love feeding people, and I love good food. But I also want to push back gently against this concept that goodness is entirely rooted in skill.

It leaves little room for what really sets each person's cooking apart, and which goes by any number of phrases ("son mat" in Korea, "made with love" in the USA, etc.) My own intuition can't be mapped against KSAs (knowledge, skills, abilities), there's no way to quantitatively measure proficiency levels for "I followed my kitchen intuition," the only measurement that matters here is the qualitative measurement: How good does it taste to you? How does it make you feel?

Intuitive cooking is empowering precisely because no one can own it or standardize it. Cooking intuitively centers us in our own practices: It is me saying "I think this needs more of this or less of that, and I'm going to follow that and see where it takes me." Rather than playing by someone else's rules, intuitive cooking reminds us to play by our own.

The value of recipes, and the challenge of writing them

I'm not saying 'toss out your cookbooks and never use a recipe again.' As with a good dish itself, using/not using recipes is about balance, and I turn to Nigella Lawson for my own inspiration in striking this balance.

In Cook, Eat, Repeat, she asks the question, "What is a recipe?"

Rather than the more common approach to formatting a cookbook (here's why I wrote this book, here's what it covers and how to use it, here are recipes), Lawson sets aside space and time to grapple with the tensions inherent in this type of writing.

She makes the limitations of recipes explicit, but she makes their affordances explicit too: She reminds us that a recipe is meant to be a guide: it's not imaginative prose or poetry, it's meant to instruct us in a process, and there is value to writing that does this.

Intuition can empower us towards self-expression through building and connecting to our skills in the kitchen: A recipe can help us continue to build those skills, hone our intuition, and continue on a path of expressing ourselves more fully.

Her discussion makes clear another issue too: that the recipe itself is subjective.

While we have a tendency to treat recipes as immovable truths, they are, like all other human endeavors, written by humans, and as such come loaded with the preconceptions and predilections of the author. A recipe is situated within a time and place within its author's life, based on however many experiments they did to perfect it, and informed by everything from their family history to their dietary preferences.

What if, instead of simply sharing our recipes, we took a page out of Nigella's book and were more explicit about our own process and context?

In my scholarly publications, I'm expected to disclose biases, conflicts of interests, etc. And in my opinion, good research discloses the author(s)' contexts and approaches explicitly, whether or not these are considered in conflict (for example, I could have chosen either of two equally workable methods, why did I pick this one? Why did I make the choices I did about population parameters? What is my own background and perspective I bring to this work, and how is that shaping these decisions?)

As scientists, when we're explicit about the research as part of a larger journey to understanding, the research becomes part of a conversation rather than an immovable truth. It offers an opportunity for change and growth, and for our collective learning.

What if we, in crafting our recipes, did the same? As Lawson says, "A recipe can be many things: A practical document; a piece of social history; an anthropological record; a family legacy; an autobiographical statement; even a literary exercise. You don't have to take your pick: The glory of food is that, beyond sustenance, it comprises a little of everything--aesthetics and manual labor, thrown in."

Perhaps, by considering these contexts and how each contributes to the choice of what to include/exclude in our instructions, how to portion serving sizes (forever a source of angst for both Lawson and myself!), how we approach offering substitutions, etc. etc. etc., we can turn our cookbooks into less of a tome and more of a conversation, both with our readers and with each other.

P.S.

I love this interview between Alicia Kennedy and Nigella Lawson from a couple years ago, where Lawson discusses her mother's intuitive cooking, and both discuss the joys and worries that come with being a writer.

I came away from the interview both with a renewed sense of admiration for two of my favorite writers, but also with a reminder of the very human, vulnerable, and learn-as-you-go nature of writing.

Next week, I'll be sharing some thoughts on tying my recipe writing practice into the larger history of recipe writing.

Paid subscribers will also be getting a special issue with some of my favorite recipes to make from Fannie Farmer's Boston Cooking School Book.

News:

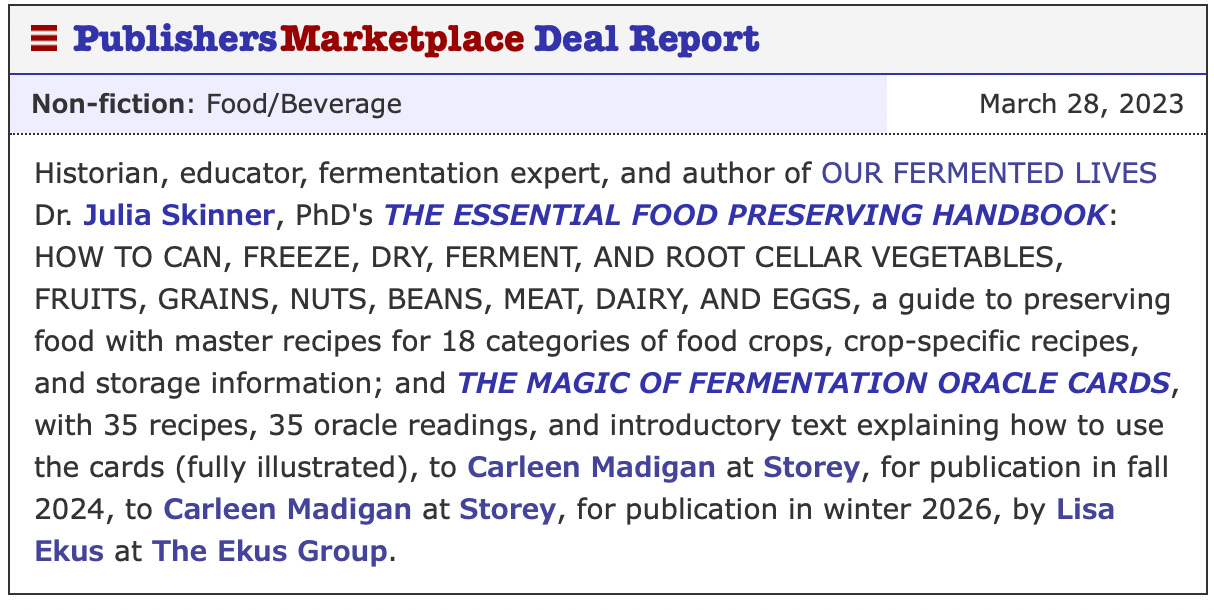

Big news first, I have two new books in the works!

The first is a big food preserving handbook, with everything from tips for repurposing scraps to practical recipes for canning and fermenting, all interwoven with my thoughts about food preservation generally and its place in history.

The second is a fermentation oracle deck, with lots of new recipes and interpretations. This one is conceptually different from the Hidden Cosmos (my self-published deck that inspired this new project!), and I'll be collaborating with an illustrator who will bring my words to life. I can't wait to see how they turn out!

With so much in the works, I've decided that Hidden Cosmos: A Fermentation Oracle + Recipe Deck won't be reprinted, though the project may re-emerge in another form in the future!

I still have some copies, but once it's sold out, it's sold out. So if folks want them, now is the time! You can find the decks on my website or on Etsy.

More big news:

I’ve won a silver Nautilus Book Award for my book Our Fermented Lives, in addition to being a nominee for Georgia Author of the Year!

It’s so incredibly reaffirming to have work I’m proud of and that I hope has a positive impact on the world be well-received, and be rewarded. More of this please!

Make: Food Zines

Summer is the perfect time for a zine making get-together: Pull together a potluck or simple dinner with a few friends, bring your favorite recipes (or create new ones together!) and make some zines to share. Maybe they're just lists of recipes, maybe they include stories and illustrations or collages.

One of my favorite things to do is to make blank zines then pass them around: Each person is in charge of one page in each zine, and at the end everyone walks away with a unique collective work of art.

I have lots to say in general about zines in relation to cookbook history, women's history, and empowering silenced voices, but for now, just think of your zine as your own addition to the written history of food, however that looks for you.

If you don't feel comfortable sewing your zine, I've had great success making zines with others using this folding and cutting template, which my friend Katie shared with me for our zine making workshop over a decade (!) ago.

If you want a sewn binding, check out the chainstitch (some great resources + tutorials are here), my go-to for attractive yet simple binding on pamphlets.

Your zine can range from glossy, full color printing (like Cook Casual, who I write a regular column for!) to black and white laser printed or handwritten. That's the magic of zine making, there's no wrong answer!

Supporting this newsletter literally makes my dreams come true, helping me devote my time to writing and to sending more and better recipes, interviews, and food stories to you. Thank you for being a part of my work!