Reflecting: What an Old Cookbook Taught me About Looking Beyond the Walls of My Work

Plus a unique holiday pie made with whole apples

(make sure you scroll to the bottom for my favorite unique holiday pie)

I'm a strong believer that revisiting our past work can help us strengthen the work we do today, whether on the stove or on the page. And even though I find most of my old writing to be pretty unengaging by my current standards, that too isn't a bad thing: It's a reminder instead of how much I've grown as a creative and as a researcher, just as one would hope.

So to round out the year, I want to spend a moment reflecting on this project, and in particular on the power of interdisciplinarity in food-related work.

I've also promised you an interview series for a while, with folks who are engaging in food work but perhaps not in the traditional ways. My first, with classical architect Rene Salas, is up and ready to read. The next, with visual artist Coorain, will be sent out soon.

Over a decade ago, I embarked on my first food history project. In what would eventually become my Center for the Book graduate thesis, and later my first book, the Modernizing Markham project was a multi-faceted experiment that brought together book art, some ill-fated attempts at blogging and social media management, and of course, time in the kitchen. I share a few recipes from that project here.

Gervase Markham (1568-1637) was a prolific English author, who mostly wrote for the country gentry on all things related to running an estate, from cooking to animal care (fun fact: he wrote so many books on horse husbandry that he was issued a court order for flooding the market on the topic). His 1615 book, The English Housewife, was one I came across in my graduate work, and I was enthralled the moment I held the volume in my hands.

I hadn't encountered anything like it before: a far cry from our modern cookbooks, the book was full of surprises: recipes written as paragraphs, inconsistent measurements, medical and surgical guidance, types of food I had never heard of before.

Nowadays I have the background to put these things in context, but it blew my mind as a first semester master's student, and my sentimentality for the book is why it often will get a mention from me when I talk about this time period.

But it's not just pure sentimentality on my part: Markham's book opened up a whole new world of possibilities to me by showing me that I could, in fact, write about and study the things I loved.

Markham's role in publishing at that time was uncommon, too: In 1615, books were more expensive than today, and literacy was lower. Many people did not have access to literacy training, either because they would be punished for being literate, or they did not have access to a literate person to train them.

Most books, then, were written with wealthier people in mind, and cookbooks in particular often (but not always!) tended towards profiling the foods of the nobility and towards their lavish entertaining, the thought being that this would be of interest to both the richest Brits and the middling folks who wanted to keep on top of trends.

But Markham worked a bit outside of those constraints (though still within plenty of others, his views on gender for example being pretty on par with the times).

Sure, he has banquet menus and will tell you how to cook a peacock, but his book is far more about frugality and reuse than many of its contemporaries.

Perhaps this is part of what drew me to him: as someone who learned to garden and ferment to stretch my funds, and for whom using food scraps often felt like a necessity, I resonated much more with a book that emphasized the importance of these activities than a book that was all about towering desserts and heavily-laden dinner tables that took up more square footage than my entire apartment.

I was also drawn to the breadth of his work. Markham gives us instructions for cooking and making herbal remedies, but also for using our spent brewing grain to feed livestock and our veggie scraps for compost.

Markham considers cooking within the whole life of a farm: seeing it as an act that feeds its human residents as well as one that cycles resources back to the earth and the animals and the house itself. He covers brewing, cheesemaking, porridge for breakfast, banquets for guests, setting tables, and the kinds of vegetables to feed pigs.

And he published prolifically: Using a technology (moveable type printing) that was by this point well established, but that saw few people publish such a wide scope of works, in such large number as he did. Markham wrote fiction, plays, household manuals, and of course, all those books on animal husbandry. Markham harnessed the technology that was available to him and used it to its best effect.

Technology was an important factor for another reason, too: Printed cookbooks like Markham’s were notable because many people at the time were still using manuscript cookbooks as references. His exploration of new(ish) media in his own work was important for understanding his work and its medium as an information object, not "just" as a compilation of ingredients and techniques.

In short, Markham was interdisciplinary: drawing on his learning across many different areas (as well as, most likely, lifting recipes from elsewhere, a common practice then as it is today) to write a cookbook that moved outside the bounds of the kitchen. So when I brainstormed what Modernizing Markham might become, my biggest priority was to do something interdisciplinary too.*

*minus the plaigarism...

Quick note: If you want to explore some other banquet menus, read The Queen-Like Closet. It was written by Hannah Woolley (1622-1675), one of Markham's contemporaries, and as David Goldstein says, the first Englishwoman to make her living as an author.

She was, according to Goldstein, "the Martha Stewart of her time," and was so popular that her name continued to appear on new books even after her death, which the publishers hoped would give them extra credibility.

the power of interdisciplinarity

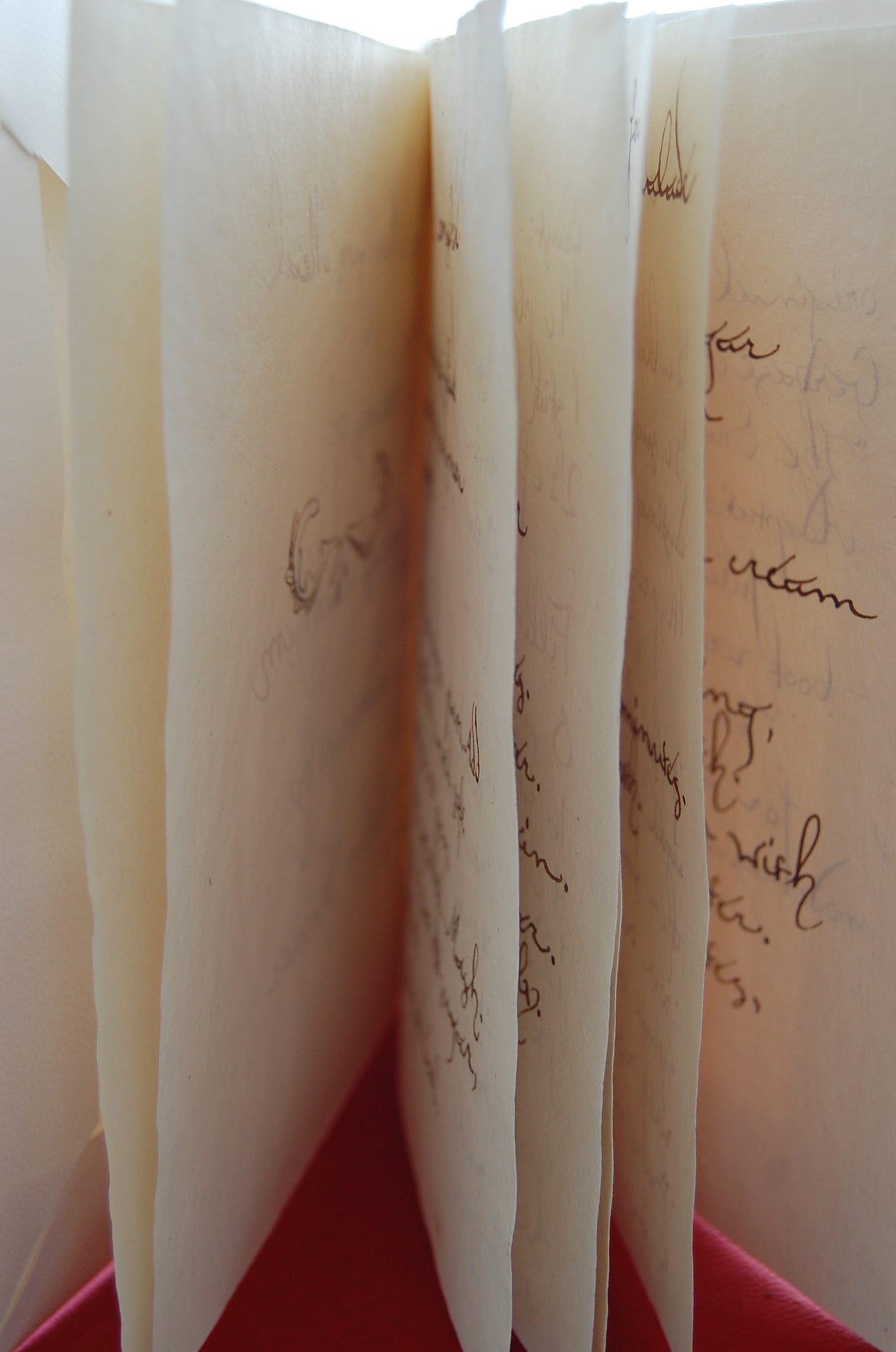

What I came up with ultimately combined recipe testing and academic research with social media and blog posts, and with book art and calligraphy using historic materials.

There are a lot of things I'm proud of about this project. The fact that I made all the banquet food in a tiny apartment kitchen from the 1890s with a floor so sloped it hurt my joints to stand there for too long. That the project involved equal parts joy and pain: scraping and saving and long hours and little sleep, coupled with intense joy, new-to-me flavors, and the thrill of discovery.

Interdisciplinary work asks us to expand our vision to a broader spectrum than perhaps feels comfortable: and doing this asks us to include our own strengths and limitations within that vision. It asks us to consider how we ask our questions, not just the questions we ask. With food, in particular, what can we learn when we take an interdisciplinary approach?

I don't mean interdisciplinarity simply in terms of " involving two or more academic, scientific, or artistic disciplines," which is the Merriam-Webster definition, though I do tend to start there.

I also mean it in terms of the modes we use to learn. I find I'm at my most creative, and doing my best work, when my academic research and writing are melded with hands on exploration of a topic: In this case, by recipe testing but also producing a handmade book.

The book, in particular, helped me consider my topic in new ways: While The English Housewife was printed, I created a manuscript cookbook, as a nod to all the recipe creators at the time whose writing was *not* considered worthy of printing (like I mentioned above, Hannah Woolley was the only woman in the entire country making her living as an author).

Writing my recipes out, knowing the care and love that went into them, within this context, was a reminder of the amount of invisible labor expected of women as well as the amount of knowledge that we've lost as a result.

How many of my ancestors, and yours, created recipes that no longer exist?

No one knows everything

During my residency with Sandor Katz, he started off by saying, roughly, "people call me an expert but it makes me uncomfortable. No one knows everything about fermentation. And if they say they do, they're lying." Katz' statement sums up one of the greatest benefits I've found to being interdisciplinary: Taking comfort in asking (and living) questions, rather than demanding clear-cut but overly simplified answers.

Interdisciplinary work asks us to acknowledge how big any given topic is. For me, I often feel like I don't know "enough" about fermentation, history, or any number of other topics simply because I so often encounter things I don't know. One of my goals this year has been to move past the negative feelings of imposter syndrome, and towards the delight of learning a new thing. Curiosity, excitement, and wonder are themes I hope to continue in 2022. And so if I have a wish for you at the end of this year, perhaps it's the same: That you view the world through a broad, multi-faceted, and sometimes confusing lens, and find wonder on the other side.

Root News

All of my online classes, as well as The Hidden Cosmos oracle deck, are 10% off through the end of the year.

Just use code HOLIDAY through January 3rd on my website or on Etsy.

For Root’s paid members, you get a 20% off all classes and decks. You can find your code here (just head to the bottom of the page).

If you're giving a class or a deck as a gift, please email me and I'll add a custom gift message for you!

Speaking of holiday gifts, the deadline to order Hidden Cosmos decks for holiday delivery is December 5th. After that I can't guarantee it will get to you (or them) in time.

Classes can be ordered whenever! Order them even the day of a holiday for the most last-minute (but still thoughtful) of gifts.

To Read

I wrote this piece for the Fermentation School (where I also teach) on building mindfulness into our morning routines.

A few book recommendations: Carlo Ginzberg's The Cheese and the Worms, Pam Grossman's Waking the Witch (also a fantastic audiobook), Wildsam city guides (a thank you to my dad for gifting me two this holiday season), The Homebrewers Almanac, Michael Twitty's Rice (and if you haven't yet read The Cooking Gene, definitely get a copy of it, too).

The current issue of Dapper Dan magazine has a piece by one of my favorite food people, David Zilber, talking about one of my favorite things, the Golden Record. I'm eagerly waiting by my mailbox for it to arrive.

This Atlas Obscura piece highlights my talented friend Megan Piorko and her work to crack a medieval alchemical cipher.

This conversation among wine experts about the end of gendering wine.

This ode to slab pizza (with hints for making your own) by Andrew Janjigian

I often share links to Alicia Kennedy's brilliant, thoughtful writing on food, but this time I want to share a link to her food itself: some warming holiday recipes, made using her Burlap & Barrel spice blend (who have *the best* spices, and blends).

To make: Markham's pippin pie

This pie is one of the recipes from The English Housewife that I still make from time to time, along with wafer cookies.

Pippins are cooking apples, and the key here is to find ones that are as small as possible: apples in the 1600s weren't nearly as large or watery as the ones we eat today.

Another reason to source small apples is that this pie calls for them to be used whole: cored and filled with whole spices and citrus rinds before adding the top crust.

The crust process is unusual for most modern bakers in that it uses hot water and fat rather than cutting cold fat into dry ingredients. There is a whole deep dive history about this that I shared a bit of here many moons ago, if you're curious (Harold McGee also talks about hot water pastry and its medieval roots in On Food and Cooking).

My recipe focused on adapting the filling, the crust recipe shared below was one graciously shared with me by Gretchen Miller, which can be found at this link.

If you're more of a visual person (and want to see my kitchen before I entirely filled it with jars of pickles), head to this link to watch me make it with Anney and Lauren of Foodstuff (now called Savor).

Here's Markham's original recipes for the pastry shell:

“On the Mixture of Pastes:

To speak then of the mixture and kneading of pastes, you shall understand that your rye paste be kneaded only with hot water and a little butter, or sweet seam and rye flour very finely sifted, and it would be made tough and stiff that it may stand well in the raising, for the coffin thereof must ever be very deep; your coarse wheat crust would be kneaded with hot water, or mutton broth and a good store of butter, and the paste made stiff and deep because that coffin must be deep also; your fine wheat crust must be kneaded with as much butter as water, and the paste made reasonable lithe and gentle, into which you must put three or four eggs or more according to the quantity you blend together, for they will give it a sufficient stiffening.”

And his recipe for the filling:

“A Pippin Pie

Take the fairest and best pippins, and pare them, and make a hole in the top of them; then prick in each hole a clove or two, then put them into the coffin, then break in whole sticks of cinnamon and slices of orange peels and dates, and on the top of every pippin a little piece of sweet butter: then fill the coffin, and cover the pippins over with sugar; then close up the pie, and bake it, as you bake pies of the like nature, and when it is baked anoint the lid over with store of sweet butter, and then strew sugar upon it a good thickness, and set it into the oven again for a little space, as whilst the meat is in dishing up, and then serve it.”

And here's my version:

For the crust:

1/4 cup plus 2 tbsp water

1 stick butter

2 1/2 cups flour

3 egg yolks

For the filling:

8 small cooking apples, peeled

16 whole cloves

The peels of two oranges

4 cinnamon sticks, halved

12 dates

Butter

1/2 cup turbinado sugar, plus more for sprinkling

1.Preheat oven to 350.

2.Combine water and butter in a pan, and simmer until butter melts.

3.Meanwhile, stir egg yolks into the flour until evenly mixed.

4.Make a well in the center of the flour mixture, and pour the butter mixture in. Stir to combine, then knead until it forms a dough ball.

5. Divide the ball in half, and roll out into two circles a bit larger than your pan (I made two crusts each with a diameter of roughly eleven inches).

6. Grease the bottom and sides of a 9″ round pan, and put the bottom crust in, making sure it covers the sides of the pan as well as the bottom.

7. Peel your apples (it's helpful to arrange them in the crust before you start so you know how many you'll need). Using a paring knife, cut a hole in the top of each apple and remove the core.

8. Put two cloves in each cored apple. Arrange in the crust.

9. Arrange the dates in the open spaces around the apples, then evenly distribute the orange peels and cinnamon sticks.

10. Place a small pat of butter on top of each apple, and sprinkle the entire filling with 1/2 cup sugar.

11. Roll out the top crust, and place on top of the pie.

12. Bake at 350 for 75 minutes, or until the apples are tender and the crust is just golden brown.

13. Brush the crust with melted butter and sprinkle with turbinado sugar, then continue baking for 10-15 minutes.