A 400 year old banquet

2021 has been extra. Your holiday dinner menu should be too.

Paid subscribers look forward to regular recipe posts like this one, delivered right to their inboxes (free subscribers get some pretty great emails, too, just no recipes).

(I'm sending your December monthly recipes along a bit early, so you can use them for all your holiday entertaining. Enjoy!)

In 1615, English author Gervase Markham published The English Housewife, a household manual with everything from health remedies (including surgery), advice on running a farm, homebrewing tips, and of course, recipes.

Markham included recipes for everyday dining, but also included entertaining menus. In true English form, some of these menus are splendid and luxurious: dozens of courses including several each of fish and meat dishes, plus preserves of all kinds and sweets, carried to the table on platters. If you are feeling particularly ambitious, you can pick up a copy of Michael Best's modern reprint of Markham and tackle one of those (make sure you have carp available if you do).

For the rest of us, I chose a banquet menu for smaller or perhaps less wealthy households. It still contains 9 courses, so there's plenty to eat (if you like vegetables, I'd recommend adding in a tenth course to include them).

The wording of Markham's original banquet menu is a good example of how different Early Modern cookbooks were in England from our contemporary cookbooks. Note, for example, that it's all one paragraph, and that the courses seem to run together for modern readers:

“I will now proceed to the ordering or setting forth of a banquet; wherein you shall observe that marchpanes have the first place, the middle place, and last place; your preserved fruits shall be dished up first, your pastes next, your wet suckets after them, then your dried suckets, then your marmalades and goodinyakes, then your comfits of all kinds; next, your pears, apples, wardens baked, raw or roasted, and your oranges and lemons sliced, and lastly your wafer cakes. Thus you shall order them in the closet; but when they go to the table, you shall first send forth a dish made for show only, as beast, bird, fish, or fowl, according to invention: then your marchpane, then preserved fruit, then a paste, then a wet sucket, then a dry sucket, marmalade, comfits, apples, pears, wardens, oranges, and lemons sliced; and then wafers, and another dish of preserved fruits, and so consequently all the rest before: no two dishes of one kind going or standing together, and this will not only appear delicate to the eye, but invite the appetite with the much variety thereof.”

Here it is formatted in a list, organized by the order in which each course was carried to the table in Markham's original description:

1. Beast/Bird/Fish/Fowl for show: This was often been a very elegant and expensive dish using expensive meat (like peacock), but goose or even chicken would sometimes stand in here.

2. Marchpane (marzipan): Traditionally this would have been baked onto a wafer and topped with different shaped pieces of marzipan and perhaps some gilding. As it turns out, I was not skilled enough to make marzipan shapes that held up, although I did make marzipan wafers.

3. Preserved fruit: When I embarked on this project, I was unclear if this meant whole fruit or fruit preserves (like jam). I now know that it means whole fruit, and The way this was worded in the banqueting menu made it unclear whether Markham meant preserved whole fruit or fruit preserves (such as jam), After some consideration, I combined this category with the marmalade (which appears later on in his list) to create his recipes for white and red quince marmalade.

4. Paste: A paste of fruit and sugar that’s been baked. This was the recipe that resulted in several failed attempts before I gave up, although I understand that it may have been successful to use something with a very high pectin content (like quince).

5. Candies: Markham listed wet suckets (candied fruit in syrup), along with dry suckets (candied fruit as we would think of it today, e.g. candied orange peels), and comfits (more like today’s hard candies).

6. Marmalade: Quince marmalade, which I've covered in the past, was my choice for this course.

7. Apples, pears, wardens (cooking pears): These were baked, raw, or roasted, and so I chose to make a pie using cooking apples, and served alongside sliced oranges and lemons.

8. Wafers: These were very thin, sweet cookies, served as a digestive at the end of a meal. The batter was filled with cinnamon and rosewater.

9. Another dish of preserved fruit

To my modern eyes, there are a few interesting things that stand out to me about this menu: One being the order the dishes were brought out, which interplays sweet and savory, and the other being the amount of fruit (but not veggies!) on the table.

Save for the citrus, it's important to note that all the fruit here is cooked. There may be a couple reasons for this. First would be purely practical: if you're hosting a holiday banquet in a fruit-heavy dining culture, but it's the middle of December and refrigeration has yet to be invented, you're going to need to bust out the preserves.

But there's a health reason, too: during this time, the medical establishment in England believed that raw fruits and particularly raw vegetables were at best unhealthy and at worse poisonous. They threw the diner's humoral balance off course by dramatically cooling and moistening their body (for more on humors, see this), potentially causing illness.

While vegetables are to be found in the great feast menus (the one with dozens of courses), they are notably absent here, and one gets the sense that the great feast menus are more savory-focused, with meat and fish as the centerpiece along with savory sauces, vegetable dishes, etc. While these fruit-heavy banquets are less popular today, there are still echoes of them in modern holiday meals: cranberry sauce and baked apples served with the main course are good examples.

This menu also illustrates the interplay between sweet and savory on Early Modern holiday plates. We tend to think of English food as being somewhat monochromatic or dull (my apologies to my English readers, I happen to enjoy your food), but this menu is an indication that English cuisine has a history of blending different flavors to create a perfect bite, just as we see across other global cuisines.

Here, sweet, savory, sour, salty, and bitter all meld together on the plate as you dish up your meat, fruits, and candied citrus peels.

Even if you don't make this full menu, I'd encourage you to try adding fruit to your holiday table, taking a nod from our English forebears. It helps cut the richness of other dishes, particularly if cooked with a bit of acid (like citrus juice or vinegar), and making food from 400 years ago will certainly be a conversation starter.

If you can find quinces, I highly recommend the jam I mentioned before, but otherwise these candied orange peels are a great addition as a garnish or pre-meal (or post-meal) snack. The wafer cookies are a traditional digestive and end to the meal: unlike many modern wafer cookies, these ones are spiced and fragrant but not cloyingly sweet.

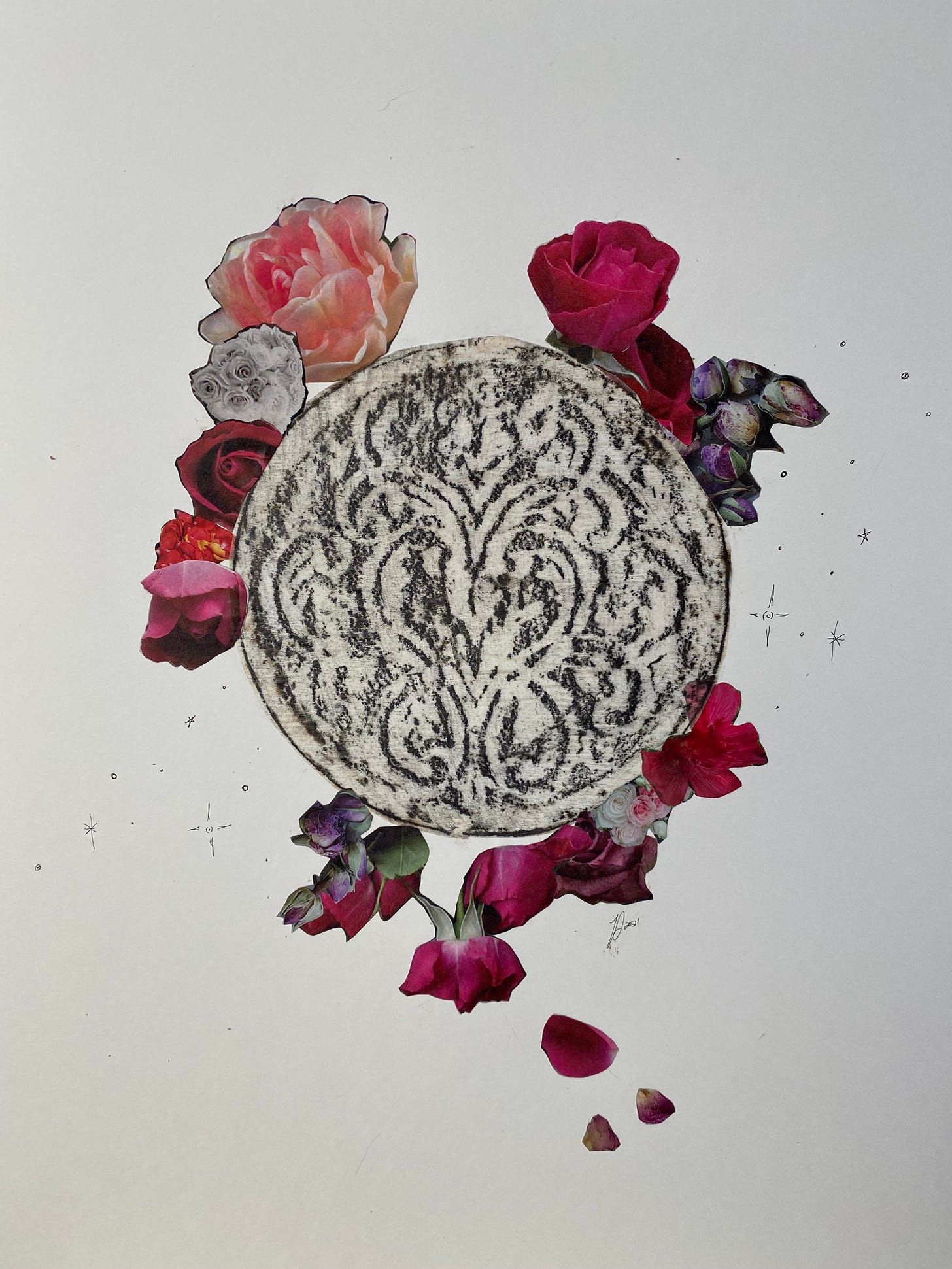

Wafers

These wafers are a beloved tradition in my home, as is my cast iron wafer iron (purchased from this museum, though they now sell a different model). Wafer irons are not a common household appliance, but they are easy to find and are sold under a number of different names, just as a "wafer iron" or by the name of a particular kind of wafer (like the Danish krumkake or Italian pizelle). You can get electric ones, stovetop ones, etc. Any of them will work here, just pick the one that seems most useful and convenient for you.

Here's Markham's original recipe:

“To make the best wafers, take the finest wheat flour you can get, and mix it with cream, the yolks of eggs, rose-water, sugar, and cinnamon til it be a little thicker than pancake batter; and then, warming your wafer irons on a charcoal fire, anoint them first with sweet butter, and then lay your batter and press it, and bake it white or brown at your pleasure.”

My recipe yields about fifteen cookies. Make sure to preheat your iron on medium-low heat for a few minutes before adding any batter.

Wafer cookies

1 cup flour

1/2 cup sugar

1 tsp ground cinnamon

3 egg yolks

1/4 cup rosewater

1 cup cream

1. Combine all ingredients in a bowl and whisk until smooth.

2. Grease your iron with a little butter, and add one rounded tablespoon of batter to the center.

3. Close the iron and hold closed tightly for about 30 seconds to press the pattern on the iron into the cake (omit this step if you're using an electric iron).

4. Continue cooking for about 2 minutes or until golden brown. If using a stovetop iron, flip the iron over halfway through cooking.

5. Allow to cool on a plate or rack before transferring the cooled wafers to another plate (this keeps them from getting soggy).

Wet Suckets (Candied Orange Peels)

‘Wet sucket’ is one of the more unappetizing culinary terms I’ve run across, but Markham and his contemporaries would have understood it as referring to fruit in syrup.

I have a fond memory of my grandfather, ever supportive of my wild research pursuits, taking a particular liking to the term. So much so, in fact, that when I talked about my recipes with him over a restaurant meal one day, he shouted 'wet suckets!' loud enough to cause heads to turn, and me to blush. I tried to loudly, and quickly, explain what they were to assuage concern on the part of our fellow diners.

Anyhow, back to the orange peels...

Wet suckets (at least by this name, people definitely put fruit in syrup previously) seem to have come about in England in the early 17th century, right around the time Markham was compiling The English Housewife. They were made using fruit, vegetables, roots (like Angelica root), and nuts. Markham’s recipe is as follows:

“Take curds, the parings of lemons, of oranges or pomecitrons, or indeed any half ripe green fruit, and boil them till they be tender, in sweet wort; then make a syrup in this sort: take three pound of sugar, and the whites of four eggs, and a gallon of water; then swinge and beat the water and the eggs together, and then put in your sugar, and set it on the fire, and let it have an easy fire, and so let it boil six or seven walms, and then strain it through a cloth, and let it seethe again till it fall from the spoon, and then put it into the rinds of fruits.”

There are a number of terms worth explaining from this recipe: wort (or sweet wort) is “the liquor made by an infusion of malt in water, from which beer and ale are fermented” according to Michael Best, or the starchy, sweet liquid we use for brewing. If you do brewing, set aside a bit of your malt for this recipe (Swap it out for the water here). Barley malt syrup is what I recommend otherwise, and can be found at most health food stores.

A few other terms in the recipe you might not know: pomecitron (a member of the citrus family), swinge (to whip or beat), and walm (to boil).

There were a few things I learned when testing this recipe. First, don’t whisk the mixture too vigorously or you’ll end up with meringue on top. It's best to strain the syrup through a fine mesh strainer to get any bits of egg out before serving. If you would like to have a slight sugar crust on the fruit, spread it on a wax paper-lined cookie sheet.

Wet Suckets

For the peels:

4 oranges

1/4 c barley malt syrup

2 c water

Using a vegetable peeler, peel strips of orange rind, being careful to not get too much of the bitter white pith. Cut into bite sized pieces (1/4″-1/2″ long).

Boil the whiskey and water in a saucepan and add the orange peels. Boil until tender (about 10 to 15 minutes). (Side note: When I prepared the ginger, I peeled it with the back of a spoon, sliced it, then cut the slices into thin strips).

Drain.

For the syrup:

2 egg whites

8 cups water (make sure its cold or room temperature)

3 1/2 cups sugar

Whisk egg whites into water until incorporated.

Heat slowly over medium-low heat, stirring frequently to ensure that the egg doesn’t scramble. While heating, add the sugar to the water, 1/2 cup at a time.

Boil for 30-45 minutes, or until the syrup is very thick (for those who have made caramel, you want it to coat a spoon in the way caramel sauce does).

Let cool slightly, then toss the orange peels into the syrup and pour the mixture into a jar.

P.S.: You get a holiday discount code as a thank you for supporting my work this year.

Just use code BYE2021 through January 3rd on my website or on Etsy.Your discount applies to all online courses, as well as the Hidden Cosmos deck.

Thank you thank you!