Theory and practice

The interplay between kitchen and page

This is the free version of my newsletter. If you want to support my writing, please consider a paid subscription for yourself or a gift subscription for a friend.

You can also join me on Patreon!

If you can't afford the paid newsletter, but it would be an asset to you in your own culinary/writing/creative journey, please reach out and we'll figure something out!

Springtime in Atlanta is truly magical. Seemingly overnight, new green growth bursts forth, a hopeful sign of warmer weather, and the sunlight hits the leaves in a way that seems to almost make them glow with their own light. Though we rarely get snow, I feel more in tune with the seasons here, whether because of where I'm at in my own personal journey, or the climate in Georgia, or both.

This year, I'm feeling especially connected to our seasons as cyclical and interwoven, and since springtime is often a time where my mind is eager to run and explore after the more restful winter months, I've been ended up spending a good deal of time thinking about interconnection in general.

I actively seek out connections between different ideas or industries we might not think to put together: It was the inspiration behind starting the Unplated interview series, and behind my own career that has led me through everything from bus driving to curating a rare book museum to working as a professor to managing a coffeehouse. All of these are interconnected in my world: There are valuable lessons to learn from each that can be, and are, regularly applied to the work I do today. For me, it's the intersection of theory and practice: my research in academia and otherwise, connected with and informed by the other work I do.

Head and Hands

My idea of theory and practice has shifted somewhat since my days as a PhD student: In that world, the theories I worked with were situated within the scholarly discourse a specific discipline (though they could definitely be applied outside of it, something I'll write about at some point in relation to food).

Practice was the work being done in the field (in this case, librarians and other information professionals), informed by professional standards and best practices but not always explicitly driven by theoretical frameworks, on the surface at least.

I'm a strong believer in the fact that our work, whatever it may be, is constantly informed by theory, and informs that theory in turn. This is particularly true in the kinds of fields I gravitate towards, whether in food or libraries, where a strong practice-based component is central to the work of that discipline. I am constantly seeking to unravel what theory and practice look like in each space I move within, but most importantly to understand their interplay.

Depending on what we're studying, our definitions of theory and practice are likely to shift: As researchers, theories and models are carefully developed and operationalized (this book, shared with me by Michelle Kazmer early in my doctorate, is a fantastic resource for understanding theory building, and the difference between theories and models).

In the kitchen (or library), our concept of theory might expand a bit to include other undergirding principles, but we're still guided by something in whatever work we do. In other words, we are always performing practice, but we're always enacting and testing theory, too. But so often, we see the artificial separation between these two forms of engagement in our discourse: As though they are two completely different things, rather than two sides of the same coin.

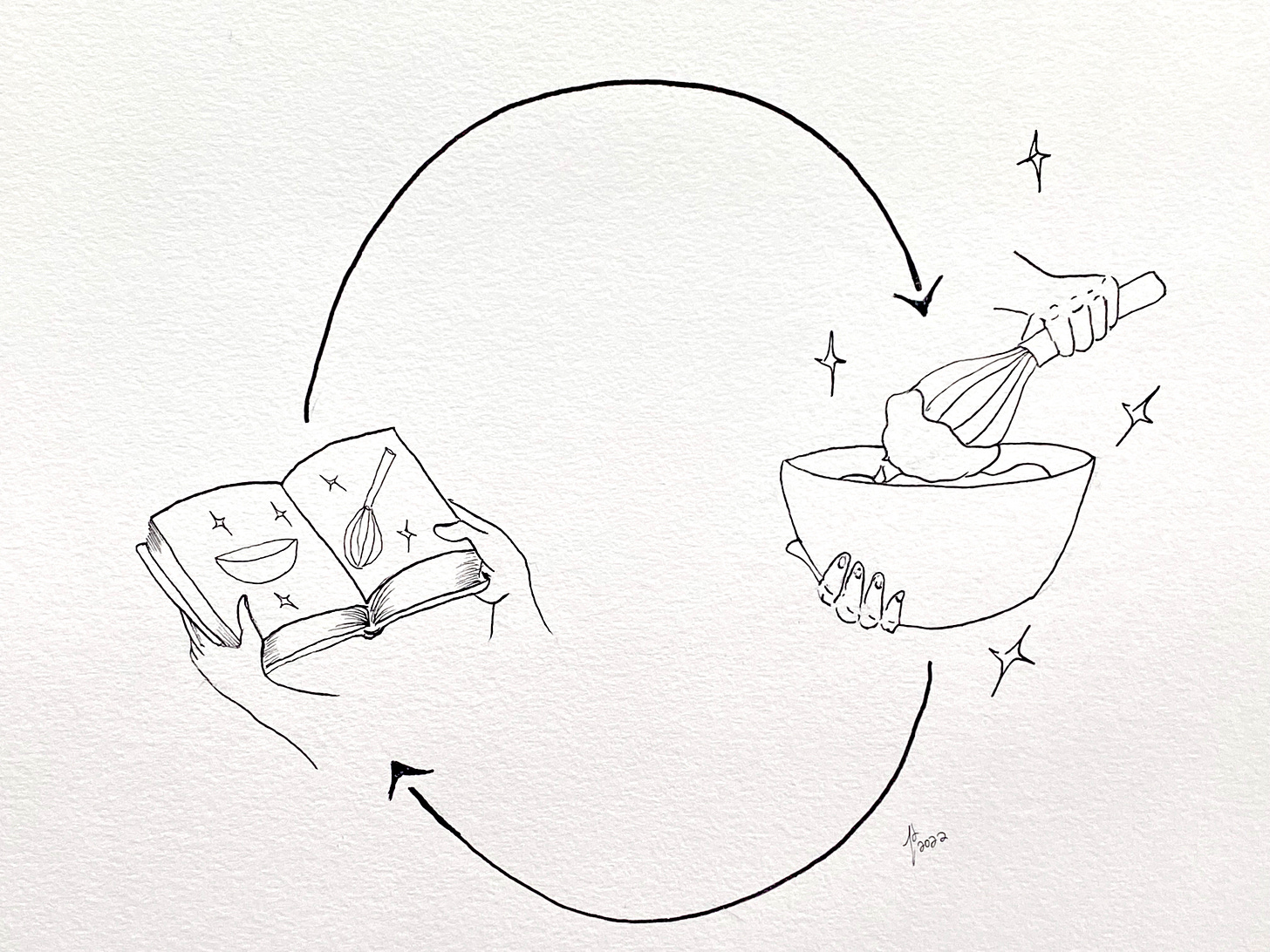

I see the two as cyclical, in constant conversation with each other. Theory, whether a formalized theoretical framework or simply the philosophy behind our work, undergirds our practice. But practice, the putting of ideas into action, in turn helps us refine theory. In a perfect world, the two build on each other. Theory and practice mirror each other, but also help us to question our current approach with a critical eye so it can become even better.

In my library work and Library & Information Science research, this divide between theory and practice was at times palpable, other times more muted, though most people understand that the two are connected. This artificial divide was often present, though, in conversations around education and professionalism in particular (why learn theory when we can just learn how to use this one database we need?)

(I have a whole rant about the shortsightedness of this approach, which I'll happily spill out over drinks, but will spare you from here).

Theory and Practice On our Plates

When I returned to the food world, I felt like most fellow writers and researchers would echo my constant refrain of "theory undergirds practice! practice informs theory!" The work we do is often interdisciplinary and informed by practice to varying extents and, at this point at least, there is an increasing recognition of the need to contextualize our work: Thinking about food, and writing about food, never happen in a vacuum.

But when we think of the theory and practice of food writing within its historical context something interesting happens. Though other fields like Anthropology have included food as a component of a larger discipline, Food Studies itself is a relatively recent phenomenon. For much of history, food was not a central subject of study, cast aside as inconsequential, both as a subject of study itself and because of the marginalized statuses of many cooks and food producers.

Throughout the edited book Cooking, Eating, Thinking, authors note that Classical philosophers like Plato, and more recent (by comparison) philosophers like Descartes are among the famous minds who dismissed food, and the various acts surrounding preparing and serving it, as unworthy of their philosophical consideration. It's one of many examples of how food and food production is erased or dismissed in favor of "more serious" pursuits.

In part because food was absent from formal theoretical discourse for so long, writing and thinking about food are devalued too. Food writing, whoever it's done for and in whatever medium, is a method through which we share our personal and cultural contexts around what we eat: It inevitably is the intermingling of theory and practice.

But it's a form of writing with a complicated relationship to our larger culture: devalued on one hand as "not real work," but real enough and needed for people to demand that food writing, and the labor behind it be given readily, happily, and for free.

The tired, ridiculous argument that people should only write recipes, not stories, on their own food blogs is one example. People's anger over paywalls for having to pay for any content, ever, is another.

What if we were to shift our perspective a bit, and consider food writing as central to this give and take between theory and practice? Would that help us value it as the important cultural asset that it is? And, by valuing the connections between culinary theories and cooking as practice, might we also value, and seek out the voices of, the people who grow and cook our food?

If you haven't read Cooking, Eating, Thinking, it considers food and philosophy using a variety of approaches. Though most of my go-to sources are more recent (this was published in 1992), I still turn to this one when thinking about the theories behind why we eat what we do.

There's plenty to unpack in the book and put in conversation with more recent work: Some thought-provoking, some problematic, some outside my scope of interests. A full deep dive is way beyond the scope of a newsletter issue, but a few highlights stand out to me.

"Theory" as Expansive

To me, theory in food spaces extends beyond the academy, and includes the philosophies, cultural norms and expectations we apply to our practice as everyday cooks and eaters. Food gives us the opportunity to think of theory in its more popular, non-academic use, defined by Oxford Languages as "a set of principles on which the practice of an activity is based."

"Theory" in this space might include a recipe or expertise that guides the production of a dish, as well as the ways we adapt or change it over time, either from learning by doing, by substituting ingredients, or whatever else. From this view, our theory (guiding principles) and our practice (the finished dish) are inextricably linked: Theory cannot exist without this practice, just as the practice cannot exist as it is without being informed by this theory.

In Lisa M. Heldke's chapter on "Foodmaking as a Thoughtful Practice", she describes a model for "thoughtful practice" that "does not begin with a (hard-and-fast) separation between theory and practice, mental and manual, knowledge and knack."

She uses her background as a philosopher to discuss this interconnection, though she also makes an argument that foodmaking may verge further into the theoretical when middle and upper-class cooks invest a lot of money into equipment and ingredients in order to make food that, as she says, is "innovative" and "artistic," a leisure activity rather than a necessity.

Plenty can be said about class and access and engagement with food, but I also think classifying everyday cooking overall as purely a matter of sustenance denies those everyday cooks the variety of motivations that draw them into the kitchen.

As Alicia Kennedy says in On Regionality, we do not all eat the same way. Why would we cook the same way either, or be driven by the same things?

Another piece that gave me pause in the theory/practice debate was Dean W. Curtin's "Recipes for Values," which compares dualist hierarchies where food is objectified ("external and non-defining," in his words) with a more participatory understanding of cooking and eating, which gives food a direct presence and value within our lives.

My big takeaway:

Externalizing food, and divorcing it from its context and history, also divorces practice from theory: The practice of eating becomes a standalone act, allowing us to turn a blind eye to the ways our eating practices are informed by history and accountable to modern systems.

Personal theories, systemic practices

This artificial separation between the practice of eating and the context behind eating is part of why I have so little patience for fad products (a meal in a can! Or bottle!) that reduce food to fuel: It doesn't matter how it looks or tastes, or what form it comes in, just that it has the correct nutritional profile.

This disconnects us from the pleasure of eating, but it also disconnects us from the community aspects of food: Who grew the lentils and peas in that protein shake? Or worked in the factory blending the ingredients together?

Connecting the practice of eating with our social contexts and philosophies of food asks us to think in these systemic terms: If my philosophy of food means, for example, that producers receive a living wage, is my choice of a mass-produced protein shake an example of my theory mapping to my practice, or does my changed practice result in a shift in theory?

When we recognize eating as an action in context, our landscape shifts. Our personal philosophies are open to review: What theories about food do I subscribe to? Are we eating in accord with the world we're trying to build? If not, what's standing in our way (recognizing that for many people, access barriers are big and real and very limiting)?

Critically examining our own 'why' of eating allows us to consider the 'why' on a larger scale. It connects my philosophy of eating to the bigger picture: If I become intentional and aware about my guiding principles, I'm able to see where those are and aren't being reflected in the world around me.

It also opens the door to examine another way practice (what do we eat/how) becomes wedded to theory (why? What cultural traditions, histories, familial legacies, etc. are in play? What systems am I participating in?)

Evolving theory and practice

Considering our 'why' also helps us connect more deeply to our practice as cooks, and that's part of what I find so valuable about food writing.

Connecting theory and practice can feel academic, but it is at its core experiential and inquisitive: traits that can exist in whatever spaces we happen to find ourselves.

Sitting at the intersection of the two helps me grow in multiple directions at once in practical and intellectual terms (again, a false dichotomy), but also allows me to understand what the drivers are behind that growth. For people passionate about food, as writers or cooks or eaters, thinking about the connection between 'why' and 'what' makes us more mindful of the world we're building versus the one we want to build.

Returning to recipe writing, our culture tends to devalue recipe blogs and the writing around them because we feel entitled to the recipes they contain, while simultaneously devaluing the labor of writing and testing as "not real" work. This minimizes the expertise of writers and is based in racist, classist, sexist systems that acknowledge the utility of work in the kitchen, but not its humanity.

In a very real way, then, this perspective perpetuates the devaluing of cooking and home-based work in general, asking that the steps that go into the 'why' remain invisible, along with most of the practice beyond the finished product.

By separating our kitchen practice from our theories, then, we are participating in a centuries-old system of erasure. By thinking of each as informing the other, and by acknowledging that our hands-on work and our writing are simultaneously rooted in cultural practice and inform the evolution of that practice, we can begin to challenge these systems and perhaps acknowledge the voices that we tend to silence.

Wedding theory to practice helps us think about our food, and food culture, in entirely new ways. For me, bringing new theories into conversation with food renews my sense of wonder and awe in this work.

When I talk with friends about food and theory and crafting meaning (I'm very fun at parties!) the first place their minds often go is to scientific principles, as applied to the practice of cooking (The Flavor Matrix, for example, or On Food and Cooking).

But we aren't limited to the hard sciences, and while I find the application of scientific principles to be a great help in my practice, where I get really excited is thinking about social science and humanities principles and the practice of food.

The production and consumption of food is, after all, inherently cultural as well as personal, and so marrying food to our theories around cultural norms or the person in cultural context is a natural (though hardly straightforward task). It is, in a very real way, the magic of the everyday.

Alicia Kennedy notes that people often point to The Omnivore's Dilemma despite it being published over 15 years ago, and despite many more nuanced and more currently relevant works have come out since. Her reading list, which offer perspectives beyond Pollan's, is well worth a visit, and her writing (plus the books on her reading list) are great examples of the ways we can gently weave theory and context into our writing without it sounding like a textbook.

My greatest sense of awe comes from anything that helps me look at the small stories behind our food and our kitchens. What did the families in this one apartment building eat over the decades, and how did it change? Why are amphoraeshaped the way they are?

Most of all, I appreciate writing that goes beyond dates and figures to consider the people themselves, and the traces of use we leave behind. I remember my frustration in the history classes of my early education, where we just memorized dates of major events, shown always through a Eurocentric lens. Where were the parts of history I could personally grasp? A battle that happened 500 years ago may or may not feel like it has much direct relevance to our lives today, but the fact that someone was cooking a dish that I still make today feels both relevant and tangibly so.

I talk a lot about the magic of the everyday, and studying the history of food feels a lot like uncovering and sharing this magic.

Perhaps our greatest magic is found in our daily practices: What are we making? How are we feeding ourselves? When does an idea turn to an experiment, then a habit, and then become tradition?

When we study the why and the what of food history, we uncover this history of the everyday, of people continuously performing life-sustaining tasks that hopefully, at least some of the time, brought them pleasure as well. It's the history of abundance and lack, of erasure and recording of stories, of the movement of products and people, and a million other things besides.

Bee Wilson's Consider the Fork is a great example of the most mundane, everyday objects and really diving in to explore them. A fork, then, is not "just" a fork. What steps did it take on its journey to become the thing we know today?

A use object will fall into obscurity, she notes, unless it serves its purpose: How many iterations of almost-forks did we have before we got to this one? And when? And how did the concept of 'fork' along with forks themselves, spread across various cultures in a way that when I say the word "fork", you almost certainly understand exactly what I'm talking about?

Of course, a fork is a cultural object and a personal one, but how often do we stop to marvel at it as such? And what other marvels can we unfold, whether in our kitchens or on our pages, when we stop to reconsider what we eat through a different theoretical lens?

Whether we're considering a fork or a recipe or our personal food journeys, how can we bridge theory and practice in our work in new ways? How can we, as writers, cooks, and eaters, continue to examine, challenge, and push forward our understanding of food using the interaction between theory and practice as our guide?

News

I've created a big discount for new subscriptions, for this month only, in honor of my 39th birthday.

My birthday falls at the end of the month, and I like to celebrate each year by giving a gift of some sort to the folks who support my work.

The best birthday gift you can give me, truly, is by supporting my work through a subscription here or on Patreon.

All classes from Root and The Fermentation School are now 20% off for paid subscribers

Thanks to my friends at The Fermentation School, paid subscribers and Patreon patrons can now use their discount for 20% off any of my classes and any Fermentation School class (not just mine).

The same is true of all the classes on my website.

I'm so honored to have friends who want to support my work, and there are so many great classes for you to explore on both sites!

(If you're a paid subscriber, I sent you your discount code in your signup email. If you need me to resend it, please don't hesitate to ask!)

This year, I’m inviting readers to join me

in brief vision journaling exercises each month to help us intentionally craft a meaningful and hopefully joyful 2022. You can learn more and see the year’s prompts here.

This month’s journaling prompt is: What does my life look like when I have a good relationship with the earth? What does that relationship look like?

To read

I loved this piece on the story of amba across four cities. Amba is a sweet/sour/spicy mango condiment, and I actually include a version I adapted to use foraged pawpaws in Our Fermented Lives. This piece dives deeper into the condiment's history than I did, and I learned a lot from reading it. And, it's a great reminder that eating something in one place is not the same as eating it in another.

This piece on fish soup around Iceland has me hungry to go back and explore all the places I wasn't able to visit on my first trip to the country.

I've just ordered medlar trees for my garden, and enjoyed this piece on how fruit was incorporated into Medieval diets.

I also enjoyed Kate Ray's recent conversation on brown rice vinegar, and the power of choosing ingredients with umami rather than those that are just sour.

Finally, Alicia Kennedy asks us to consider regionality, food, and "infrastructures of abundance," really the perfect phrase for this conversation.

Atlanta-based Senegalese chef Cheikh Ndiaye was recently featured in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution along with some of his delicious recipes. His food is always a delight, and if you’re curious about Senegalese cooking these are a great place to start.

If you’re in/near New Orleans and want to try Senegalese food, check out Dakar Nola (they also have an upcoming Juneteenth celebration along with their regular pop ups). Chef Serigne Mbaye uses food to explore the connections between New Orleans and Senegambia. Both chefs are incredible folks with big hearts and a ton of talent, and their food is definitely worth experiencing.

To Make: Bitters Inspired by ‘In the Desert’

In the Desert

BY STEPHEN CRANE

In the desert

I saw a creature, naked, bestial,

Who, squatting upon the ground,

Held his heart in his hands,

And ate of it.

I said, “Is it good, friend?”

“It is bitter—bitter,” he answered;

“But I like it

“Because it is bitter,

“And because it is my heart.”

Earlier this month I discussed the history of bitterness as a flavor, and particularly the ways in which it is and has been both revered and reviled in Western cuisines, where bitterness often but not always exists in the background.

Stephen Crane's In the Desert sprang to mind as I wrote: a complex but ultimately loving relationship with bitterness in the form of a poem.

As I wrote, I felt eager put the poem in conversation with bitters as a food. What new insights do we gain about literature and poetry when we envision edible representations of them?

Here, I imagine the idea of Crane's creature, and the bitter but beloved heart, in a spicy blend reminiscent of deserts in the American Southwest. These bitters are absolutely stellar with bourbon, or just mixed with ginger beer for a non-alcoholic option.

If you're curious how each component connects to the poem, read on (otherwise just scroll a bit to get to the recipe):

The dried chile, purchased during a winter trip to Santa Fe, is used here to mimic the dry heat of the desert in which we find our creature. If you can find New Mexico chile (sometimes called hatch chile), it works best here, but whatever mild to medium dried red chiles you prefer (whole, not ground) can be substituted.

The blood orange peel represents the heart our creature is eating, with the added bonus of rounding out the heat and bitterness of the other ingredients with a touch of sweet and sour.

Cacao and mugwort both add bitterness in different ways, mimicking the creature's relationship to bitterness in the poem.

Mugwort (artemisia vulgaris), often invasive in the Southwestern US, brings a bitterness that speaks to the geography of the desert itself. It's here to mimic the conversation between Crane and creature: the flavor of the flora in the desert backdrop itself.

All the flavors are rounded out with cacao, a bitter food that we culturally value as decadent and rich, the source of cravings and the basis of many favorite desserts. Cacao takes us to the end of the poem, where eating bitterness becomes acceptance of bitterness, and even a love for it as it becomes a part of ourselves.

In the Desert Bitters

1 dried, whole red chile

2 two-inch strips blood orange peel

2 tbsp cacao nibs

1/2 c packed dried mugwort leaves

vodka

1/2 pint jar

-Pack all ingredients except vodka into your jar, leaving about 1/2-1 inch of headspace at the top.

-Pour vodka in to cover your ingredients completely (they may float once you fill the container all the way. That's alright!)

- If you have a fermentation weight, put it on top to weight your ingredients down before you add your vodka. If you don't have a weight, plan to gently stir or shake your jar every day or two.

-Seal the lid of your container tightly.

-Set out of direct sunlight and allow to steep for 3-4 weeks, or until the flavor is as strong as you'd like

-Strain through a fine mesh strainer and decant into dropper bottles (or just return to the jar, if dropper bottles aren't available).

I absolutely adore turning things I read and watch into food and drink. If you happen to do so as well, I would love to see what you make, either on social (@rootkitchens) or just by email. Thank you!