Last month, I shared some thoughts about turmeric and symbolism in food, and about food as information. As I wrote about color and flavor and symbolism, the next stop on that train of thought was about the interconnection between art and food, and between our perception of food, and food writing.

We're in a moment where sharing the recipe is not necessarily enough.

People want something evocative: We want mouthwatering images, perfectly set dressed, lit, and framed so we can almost taste that perfect bite. Or, we want photos of the food in action: the bustling street vendor cart handing out ice cream or the polished restaurant kind enough to share their recipe for bouillabaisse.

When our words and images are often so interconnected, where does food as aesthetic end and food as consumable begin? As recipe creators and food writers, how do we perceive our work as not only literary art but visual art as well?

I haven't arrived at any final answers, and am not sure if any even exist, but I have started to probe the edges of the question, and hope you will too.

As both an artist and a writer, I'm keenly aware of the interconnection of my words and images, and of how we as readers tend to treat both kinds of information.

In articles on food, it seems we often see illustrations as a translation of the text: something that incorporates key elements of the writing into visual form but does not necessarily offer additional layers of interpretation or analysis. The words are considered quite separate from the art: They are there to inform or entertain, but unless we're reading fictional prose or perhaps poetry we may not think of those words as art.

What happens if we shift that perspective? What if we extend this not only to include our narrative writing, but even to recipes, perhaps some of the most desired and simultaneously undervalued (financially, at least) pieces of writing out there?

All writing asks us to take part in a creative endeavor and put something new into the world. While outside the bounds of narrative storytelling (or is it?) a recipe is inherently generative: Recipe writing is creative in the sense not only that we are making content but calling upon any range of faculties (Problem solving! Curiosity! Ingenuity!) to do so.

"Art" is not inherently highbrow or conceptual: art can be whatever we make it, and sometimes what we make is something purely didactic, yet still an act of creation and thus creativity. Built from love or necessity or whatever else, your recipe for snickerdoodles may not be the first or best, but it is yours, a fact worthy of pause and reflection.

Bridging our words and our images

Acknowledging recipes as explicitly creative endeavors is useful, but is only part of the picture. Particularly in this visuals-heavy age of publishing (and marketing, and social media, and...) the images we choose to connect with those words matter.

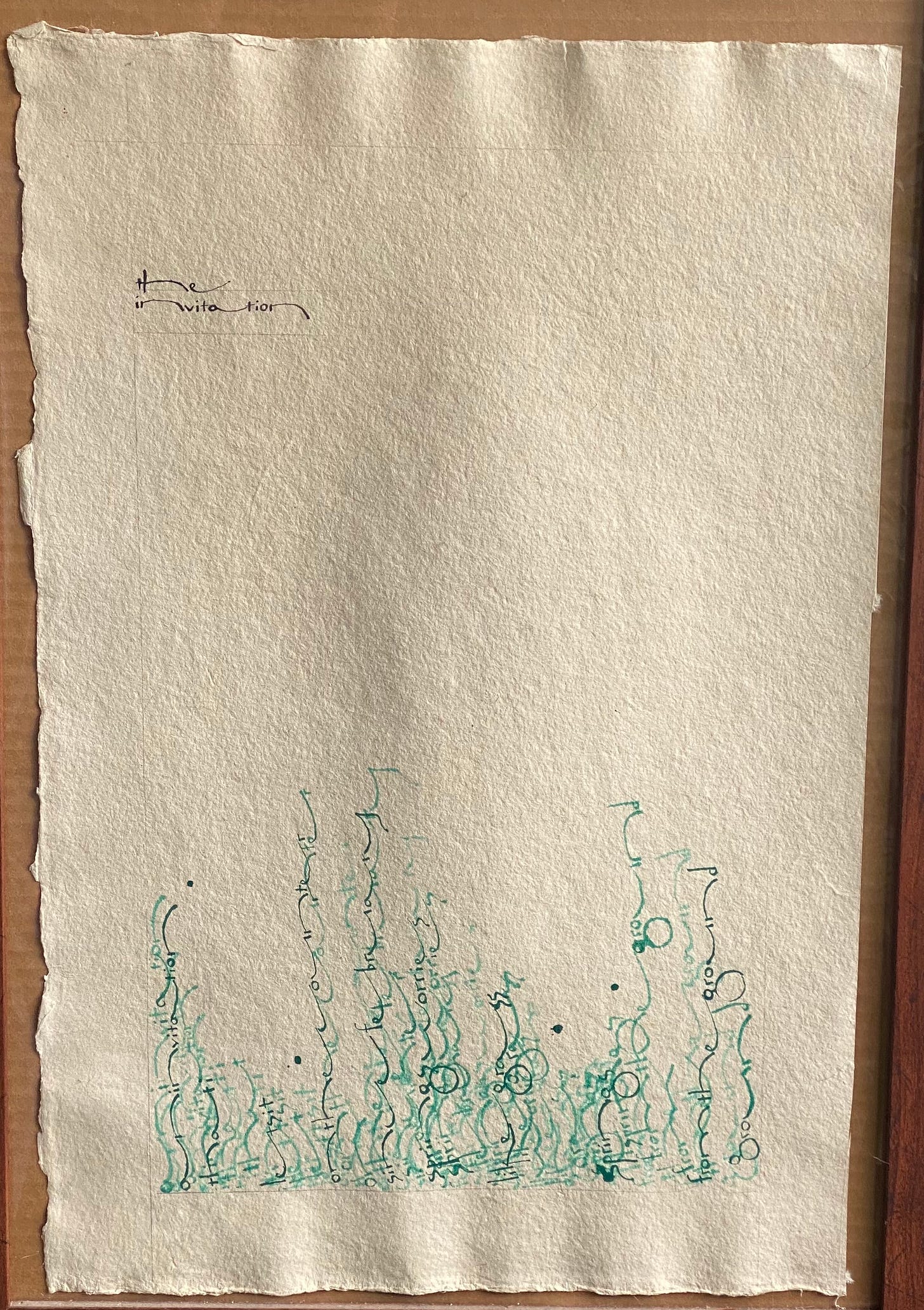

The ways our writing and art intersect can be literal, but it often isn't (see the non-food example below: a poem I wrote that’s nominally about grass, done in calligraphy to look like...grass).

How can we use the visual to express more about a piece? To dive more into the author’s process (or the editor's)? In particular, what images add to the story we're building and which ones detract from it?

With recipes, in particular, what can we glean by connecting visual elements outside the usual avenues?

Recipes are an interesting case study here because the recipes themselves are often quite utilitarian: they are of far less value to us if we can’t actually use them. But they also spark our creativity: Inspiring process, spicing, plating, etc. whether or not we follow it to the letter.

I thought about this a lot when looking at this newsletter’s visuals, and realizing how using stock photography or even my own photos often felt like it detracted from the recipes and stories I wanted to share.

After all, this space is not solely focused on recipes, so having nicely curated photos of a finished product alongside how tos doesn’t feel as necessary as it might for, say, a cookbook or a recipe blog (though those also share stories, and for good reason).

Even in recipe-heavy issues, I felt like photos were detracting: using them was a way to say ‘here’s how I envision this looking’ and in so doing, placing implicit restrictions on how someone else might construct the finished dish.

Are there ways that are historically accurate? Sure. Ways that probably make for a more balanced bite or Instagram-worthy aesthetic? Yep. Does any of this matter if you’re just getting in the kitchen to play with a new method and see where it takes you? Maybe, maybe not.

(As a side note, I rarely use recipes in my own cooking, not as some ‘tough chef’ flex but just because it’s easier and more playful to get in and explore. It’s nice, then, to write recipes and think about how that exploration might be explained and recreated by someone else).

Photos are, at least to an extent, open to our own interpretation, too: while styled to evoke a certain mode of engagement, as with any good design, what we take away is still shaped by our opinions, tastes, and experiences.

Ultimately, Illustrating my own writing shows you what matters from the vantage point of the author. And, like the text, it is also open to each viewer's interpretation while supporting play and experimentation over mimicry: In itself a nod back to how we used recipes in the past (something I'll be covering very soon).

Root News

Big news first: My next book, Our Fermented Lives: Fermentation and the History of How we Eat, Heal, and Build Community is available for preorder!

The preorder page has links to Bookshop.org and IndieBound: My preferred sources for buying a book online.

I'll be signing and selling copies of The Hidden Cosmos Oracle deck at the International Association of Culinary Professionals conference later this month. Stop by and say hi (and grab a deck) if you're attending!

If you aren't, you can find a signed copy at this link.

I'm also starting to send out holiday wholesale orders for The Hidden Cosmos, so I can get them to shops before the holiday shipping rush.

If your shop would like a unique culinary book/deck for holiday shoppers, wholesale orders are still open!

Wholesales are $21/deck: to place an order, email hello@root-kitchens.com

To Read

I love this interview between writers Alicia Kennedy and Andrew Janjigian (who runs Wordloaf), particularly the nuance they brought to ingredient sourcing and accessibility.

As Kennedy says, "we're all constantly trying to find this balance—or we're all, I think, people who try to care both about accessibility and taste and ecology, and trying to juggle all of these ideas at once. You have to think about what's good for your local ecosystem, and what's also realistic."

Frances Moore Lappé says, "I’m not an optimist — I’m a possible-ist,” she says. “Everything is possible, we just have to make it happen.” I appreciate this piece on her work and on changing our food systems for the better, and the acknowledgement of the inherent healthfulness of ancestral cuisines writ large, calling into question our uplift of Western cuisines (e.g. Mediterranean) as the only truly "healthy" diets.

Stone soup has a long and intercontinental history. Here's a primer on how to make your own (thanks to the ever-amazing Cassandra Loftin for sharing).

I've been re-engaging with Chefs Wild as I gather wild foods this autumn, along with my constant engagement with Mallory O'Donnell's How to Cook a Weed.

As always when I mention foraging, I humbly share a reminder to be sustainable in your practice, and mindful of how our laws and history shape who can safely be out in natural spaces today.

And finally, a reminder of two useful food history research tools: The Sifter (a searchable database of food history sources) and The Food Timeline (food-related timelines along with helpful bibliographies).

To Make: Victorian funeral biscuits

In the paid newsletter this month we talked about living foods and their use in rituals for the dead.

The Victorians were obsessed with death, living at the confluence of modern technologies (like photography) that made the dead easier to document and remember, while still at the dawn of medical advancements that reduced mortality rates, especially among children (like widespread vaccinations, not to mention that bloodletting was still a thing, though was in its last gasps as an established medical practice).

In this space between two worlds, where the old ways that preceded the Industrial Revolution were being replaced by larger-scale, more efficient industrial processes, but the traditional mindsets around life, death, and relationships were often still clung to (like Queen Victoria’s years-long practice of dressing in mourning clothes), it makes sense that people would fixate on one of the few things that felt certain in a constantly changing world.

While many people fear death, one wonders if it helped make things feel more relatable or in control: As if we could understand this process and in so doing understand a rapidly shifting world.

Funeral biscuits (sometimes called seedcakes in older cookbooks as well, though seedcakes weren’t only eaten at funerals) were popular in England and parts of America beginning in the 1600s and through the Victorian period.

These cookies were given to mourners attending the funeral and sometimes to passers by (in some cases, they were even delivered door to door with the news of a neighbor’s passing). The cookies were wrapped in white parchment with a black wax seal, and sometimes printed with information about the deceased. The wrapped snacks served as both a favor to take home and a token of remembrance.

They were almost always purchased rather than made at home: While some folks did make their own, it was a sign of wealth and status to outsource funeral cookie making.

And, in true Victorian fashion, the upper classes created their own separate definition for what a Victorian funeral biscuit (or cake, or cookie) was, effectively using food and its correlates as a tool for exclusion, also seen in complicated etiquette guidelines and the mind-boggling number of specialty utensils that graced their tables.

The wealthy went for a sponge cake/ladyfinger-style cake, while the working classes went for a more shortbread-style cookie (since we made sponge cake-style treats a few months ago, I’ve opted for the shortbread).

In both cases, we see molasses, ginger, and caraway as common flavoring elements.

One final note: Typically, these cookies were pressed into a mold that would impress a cross, cherub, or other funeral-appropriate emblem on them. I, alas, do not have such a mold, but if you do, this is a great place to use it!

1 tsp ground ginger or finely minced candied ginger

1 tsp caraway seeds

1/4 tsp salt

2 sticks butter, softened

1/2 c granulated sugar

about 2 1/2 c flour

-Preheat oven to 350.

-In a bowl, cream together the sugar, salt, spices, and butter.

-Add half the flour and mix. Begin drizzling in remaining flour until it’s the consistency of a stiff dough (the exact amount will depend on humidity and a host of other factors). If your dough gets crumbly, add the tiniest splash (about a tsp) of milk.

-To shape the cookies, you have two options:

-Option 1: Turn the dough out onto a floured surface and roll it out until it’s 1/2 inch thick. Use a cookie cutter to cut out the cookies.

-Option 2: Lay 2 pieces plastic wrap down on the counter. You want it to be long and wide enough to roll your dough up. Put half the dough on each piece of plastic (2-3 inches from the top), and shape into a ‘snake’ by gently rolling or pressing the dough. Take the top edge of the plastic and fold it over the dough. Press the dough firmly in the plastic until it’s a uniform round shape. Wrap tightly, refrigerate for half an hour, then unwrap and slice into 1/2 inch thick circles.

-Bake the cookies for about 15-18 minutes or until set and slightly golden.

Your art is so beautiful and you've written a great truth I share. I'm glad I've subscribed!