When I wake up in the morning, the first thing I notice is that my pillowcase tastes like blueberries. It’s a familiar flavor, one I’ve tasted a thousand times before, just as I’ve tasted the lacquered tang of the walls or the soft, creamy lemon of the lampshade.

I've yet to begin my day by physically eating a pillowcase or a lampshade, but my brain is wired in such a world that each and every physical thing in this world has its own unique flavor.

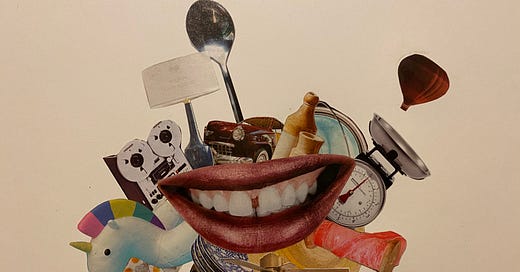

For synesthetes, the world exists at the intersection of sense and sensation.

Synesthesia is when you experience one of your senses through another sense (or multiple senses). Rather than being pathologized, synesthesia has mostly been considered a curiosity: we don't really see attempts to 'cure' it or to ostracize synesthetes in the historical record.

The first record of synesthesia symptoms goes back to 1700, and we start to see the term itself used in the 1860s. Our definitions have changed over time, but a persistent idea has been the idea of "crossed wires" or of definitions like "seeing sounds" that relate to a specific type of synesthesia.

For gustatory forms of synesthesia, non-food things trigger taste experiences. The most studied gustatory forms seem to be lexical-gustatory and sound-gustatory, basically people who experience words and sounds (musical or otherwise) as flavors.

Gustatory synesthesia, in whatever form, is among the rarest, but there is another form of gustatory synesthesia that's barely been studied at all: visual-gustatory, where everything you look at has its own flavor.

It's beautiful, confusing, exhausting, and wonderful all at once (if you've ever watched Sorcerer's Apprentice scene in Disney's Fantasia, with all the dancing mops and buckets, it kind of feels like that). And it makes for some really interesting creative exploration in the kitchen.

When all things have a flavor, going out into the world can be equal parts overwhelming and magical. I get insights into the world few others do: drawing connections between the physical objects in my world based on flavors that perhaps no one, even other synesthetes, experiences in the same way. Even the wrapping on a chocolate bar tastes different than the chocolate bar itself, meaning I've already experienced a completely separate flavor sensation before a piece of chocolate ever enters my mouth.

While individual objects have their own flavor, these come together into an overall experience, just as individual ingredients come together in a meal. Any space, then, is a symphony of flavors, and I have consciously and unconsciously crafted my own spaces accordingly. My bedroom fixtures and the mural on the wall all come together to create a flavor that's part dessert, part fruit smoothie.

The grocery store, on the other hand, tastes grating and stark to a point it sets my teeth on edge: The combination of the acrid tang of metal shelves and the startling sharpness of fluorescent lights. My bedroom tastes soft and inviting: The grocery store is anything but.

Not everything tastes like a recognizable food, though, and this makes trying to describe those flavors frustrating at best, particularly when the flavor you get is the flavor of another object non-synesthetes have no reference for.

My closet doors, for example, "taste" exactly like the drop tile ceiling in my old apartment, despite their different textures (and the fact that my closet doors are far cleaner than that ceiling ever was). What do both of those taste like? A bit bland, but what flavor is there is smooth and milky; almost sweet.

A beginner's guide to cooking everything from wallpaper to wheels

What happens when you can taste the whole world, with each object, living being, and space having its own nuanced 'flavor'? And what does that do to the food you cook?

Making lavender caramels, for example, isn't just something I do because lavender can add a nice floral bite to desserts: The visual flavor of the small, spiked flowers contrasts with the smooth ripples of the caramel's surface, just as the 'flavor' of both colors (the particular taste of cool purple versus the quite different flavor of warm honey-colored caramel) go into account.

Each dish is based on the entire sensory experience of that ingredient: how the texture, color, and even shape taste when I look at them. Sometimes this offers a pleasant sensory surprise (vanilla rhubarb sauerkraut might not be the first thing you'd want to try, but is one of the better foods I've ever made), but sometimes a flavor as it exists in my mind is a far cry from the actual flavor combination itself (see: chocolate cake with raw tomatoes).

Often the dishes turn out better than I expect, but there is another benefit as well: Cooking in this way asks us to engage with the entire sensory experience of an ingredient, and to bring some imagination into the mix.

So how do I translate the flavor of an object to the flavor on my plate? I start with basic tastes to begin categorizing what I'm looking at (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, umami). Does it have one of them? all of them? What about texture and temperature?

Then, it's time to start mapping it to my edible world: What other foods remind me of these tastes and textures? Looking through cookbooks, digging through resources like The Flavor Bible or the Flavor Matrix, or Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, have all helped me single out what I'm tasting.

I've noticed a regular meditation and mindfulness practice helps too, perhaps because I'm more intentionally engaged with the world around me and more tuned into my surroundings and my connection to them. If you, too, are a synesthete, this would be my number one tip for connecting more deeply with your intersecting senses.

Learning to taste it all

Unfortunately, very little seems to have been written about gustatory synesthesia writ large, and seemingly nothing about how to translate the experience for non-synesthetes. With that said, here's my attempt at some "how tos" to help you explore your world in a new way:

First things first: Pick an object. Just one! You can always add in more later, but this will help keep things fun and less overwhelming.

Start out by thinking of what the object reminds you of. What is its color? Shape? Size? What foods can you think of that are similar colors, shapes, etc.?

While not everything I taste corresponds to the color of an object (a yellow curtain doesn't necessarily taste like a lemon or an ear of corn), color, shape, and texture can be a great place to start imagining the flavor of the world around you if you've never tried before.

Let's say, for example, the object you have is a wooden cutting board. Maybe it's the color of butterscotch or caramel, and might even be a similar shape.

Thinking of texture and temperature can help a lot, too: Is the surface hard and smooth, like a table, or soft and warm, like a fleece jacket? Do you imagine it's warm or cool to the touch?

With our cutting board example, the texture of the wood can help us imagine if we might associate it with a hard caramel candy versus a soft and chewy one. If we're imagining a softer caramel, perhaps we're also imagining something warm like a caramel sauce.

There are no wrong answers here, just whatever your imagination holds!

I've tried this out with a few brave non-synesthete friends, and I've been surprised that the range of answers in some ways mirrors those I find when talking with fellow synesthetes. It turns out that, even without synesthesia, you can imagine the flavors of the world around you and come up with some pretty nuanced and detailed results.

It seems that typically each person doing this exercise will focus on a different trait (like texture or color) and let their imagination lead the way from there.

But what I also find interesting is that, even for non-synesthetes, flavors I find jarring feel off-putting for them too: When asked to imagine the flavor of the local grocery store shelves, one friend came back with "disgusting and gritty and sour, like stale candy." We each encountered different flavors, but the uninviting feel of the space left a bad taste in both of our mouths.

Most exciting for me, though, is that my non-synesthete friends get a glimpse into some of the magic and wonder I feel when I describe the flavors of my world. One friend noted they had seen, but never really observed, their table before. The scratches and dents, the smooth finish, the warmth of the wood, all ultimately helped her formulate a bread pudding: The crunch of the top of the dessert contrasting with the warmth and softness underneath.

I'd encourage you to take a few minutes today to imagine a food's taste (or, if you're a synesthete like me, to try to connect the taste to a food you already know). Will you come up with a definitive answer? Maybe not. But will you come to appreciate the world around you a bit more? Almost certainly.

To read

Apalachicola oysters, and the town of Apalachicola itself, are near and dear to my heart: My great grandfather and my grandma both lived in Apalachicola and conducting research on the oyster populations, and it was one of my favorite places when I lived in Florida. If you haven't already, I highly recommend this piece on the decline of oyster populations and the correlating decline in multi-generational knowledge from the communities who make their living off oystering. It's sobering and, for us in Atlanta, an urgent reminder of the impact our city's growth has on ecosystems farther south.

This piece on Montana's oldest forests is a reminder of how much forests nourish our world spiritually as well as physically. My favorite quote: " When a forest gets to be this old and untouched, it becomes something more than a forest. It becomes what we would think of as a mind, with history, knowledge, memory, and foresight. It has a pulse, and a spirit incomprehensible to us—but we can feel it when we’re in its presence."

Sophie Strand has quickly become one of my favorite authors and thinkers, whose work asks us to expand our understanding of the ecosystem and our place in it (I'll be publishing my interview with her next month). This piece, on writing ourselves and our ecology into our stories, is one I've been rereading and digesting recently.

In my recent class on preserving cookbooks and family recipes, I pointed to an online preservation course that's one of my go-tos for information on book/paper/photo preservation and disaster remediation. I highly recommend it if you are stewarding materials you'd like to preserve in the long term.

For a somewhat different take on synesthesia, I've started rereading Aimee Bender's The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, about a woman who can taste the emotions, hopes, and dreams cooked into any food she eats.

A birthday celebration

On the Spring Equinox in 2018, after months of scheming and dreaming, I launched Root, rededicating myself to culinary spaces and to my identity as a food writer.

A big theme I've felt around this 4th birthday is dreams:

Birthdays are a time of dreaming of the year ahead, but so too is the Spring equinox, as a time when we can dream of summer and see the manifestation of those dreams slowly unfolding in our gardens.

I'm so grateful for all the support I've felt for this dream, and for all the magical and unimagined places it's taken me and continues to take me!

Through the end of March, please use the code DREAMS for 20% off everything I've made for Root with your support over the last four years:

This newsletter, my online store, and on Etsy.

Ferment and chill is a space I've hosted a few times during the pandemic, where we gather together for a low-pressure space to create food by hand in (virtual) community.

It became one of my most popular classes, but since I have students all around the world, scheduling conflicts meant not everyone could join who wanted to.

I'm very proud to share that I've now launched Ferment + Chill as a self-paced, online class!That means you can enjoy the recipes and prompts, and suggestions for crafting your own calm, creative space, on your own time.

I very firmly believe in the power of working with our hands to reduce stress and help us care for our mental health, and I hope by making an affordable, flexible version of the class it will help more people reap those benefits.

Learn more and join the course here.

And finally, this year, I’m inviting readers to join me in brief vision journaling exercises each month to help us intentionally craft a meaningful and hopefully joyful 2022.

You can learn more and see the year’s prompts here.

This month’s journaling prompt is:

Who in my community do I most want to help, or work with? How am I laying the groundwork to be a good ancestor?

To make: Chilled Mango and Coriander Sauce

I sometimes think of my synesthesia as creating a waking dream space, so it's appropriate this month to share a simple recipe that came to me in a dream several years ago and has been a staple since.

This sweet and salty, lightly fermented sauce is great served cold for dipping fruit, pouring over fish, or adding to your breakfast yogurt. For a sweeter flavor, ferment for just two days: If you want it more sour and funky, let it go for longer.

1/4-1/2 tsp whole coriander

3 mangoes, peeled and cut into 1” cubes

1/2 tbsp sea salt

1 qt water

-Place your coriander seeds in a packet so they're easy to remove later: reusable spice bags, paper tea bags, or several layers of cheesecloth tied at the top with twine work great for this.

-Combine your ingredients in a large jar or crock

-Cover and allow to ferment for two days, stirring gently twice a day.

-When you're ready to make your sauce, remove the coriander packet and discard

-Pour mango and water in a blender (use only half the water for a thicker sauce) and blend until smooth. Serve chilled.

-Can be stored in the fridge for 1-2 weeks.*

*It's natural for this sauce to separate in the fridge. Just shake or stir to combine before using.