I spent years working in libraries. And specifically, I spent years working in special collections, stewarding and organizing everything from civil war diaries to Quaker abolitionist papers to medieval manuscripts and eventually, an entire collection of rare books.

Sometimes, the books I would acquire weren’t ‘rare’ or even necessarily old, but they fit into the collection well and added some needed context or historical information.

One such book, Questions About the Oceans, was published by NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, in 1965.*

This slender paperback volume was dedicated to questions commonly received by marine scientists about the world’s oceans and the life within them. It is organized by question, with a helpful index of questions at the front for easy browsing.

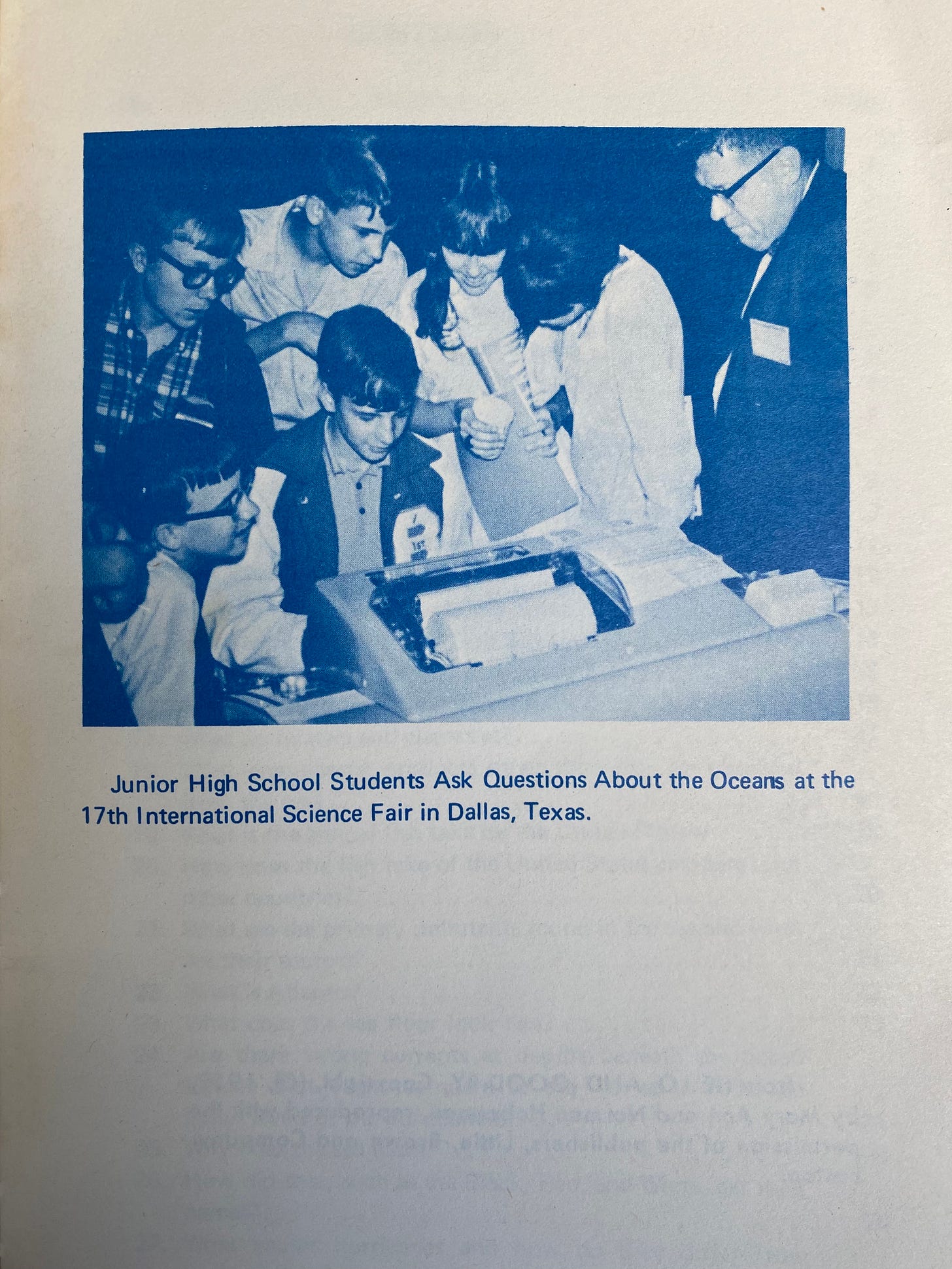

Well organized and useful, yes, but what is most interesting about this book is what spurred its publication in the first place. In 1966, NOAA staff exhibited at the 17th International Science Fair in Dallas, TX.

The display included a Teletype machine, linked to an oceanic research database in Washington, DC. People asked the machine questions, and it would spit out responses.

The machine was a hit, and the questions in the book were compiled from those asked at the fair as well as the most common questions they receive the rest of the year. It's a great example of using tech to make information accessible, and using what we learn to continue to teach others.

I’ve always found this book fascinating, and in my past life I planned to do a joint exhibit on it. Using the book as a starting point, drawing in other books as well as visual art and performance pieces connected to specific questions.

While the exhibit never came to pass, my curiosity remained, perhaps in part due to my lineage of marine biologists, and to my grandmother in particular, whose extensive shell and specimen collection lives on in my home.

In my current food-focused life, my curiosity shifted towards how the questions might help us draw connections with what, and how, we eat. There is power in questions, and particularly in how asking a question sparks further exploration.

By questioning, we allow our curiosity to blossom, inviting in more questions and lengthening the path of discovery.

What curious directions might we move when we encounter a list of questions someone else created? What about when we encounter a whole book of them?

What if the questions aren't about our area of expertise, per se? How do they elicit curiosity within our own areas of interest?

To find out, I’ve chosen to highlight several of the book’s questions and their answers, connecting these to the questions and answers they might offer us about what's on our plates.

The further questions I ask are ones for which answers may exist, and which you may even know the answer to (if you do, I would love to hear it).

What makes the ocean salty?

This first question immediately brought to mind the idea of changing landscapes, something I've touched on in recent issues.

Environmental succession is the idea that our natural world changes over time. The longer a specific environment exists, whether a forest or a tidepool, it will undergo a series of changes as new species are introduced or grow, and as these and other factors influence the environmental conditions.

What is able to grow on a cool, shaded forest floor is far different (and perhaps more fungus-heavy) than what might grow in a sunny field full of new saplings.

What is fascinating about this entry is that scientific findings on ocean salinity flew in the face of this idea: Initially we thought that seawater's salinity itself was a part of environmental succession (going from fresh water to salt), but instead we see relatively stable salinity to which the rest of life adapts.

There are some curious insights one might draw from this particular tidbit, in either the direction of adaptation or in the direction of inflexibility: the setting of boundaries that serve you/your purpose, and insisting they be adapted to. Which serves us in what settings? And do the ways in which they serve us change over time?

As far as food, this question urged me to consider environmental succession on a micro scale rather than a macro one.

Our microbiome, our own physical ecosystem of microbes, changes over time, shifting with the microbial inheritance from our mothers upon our births, and again and again as we nurse, grow, and encounter new places and experiences.

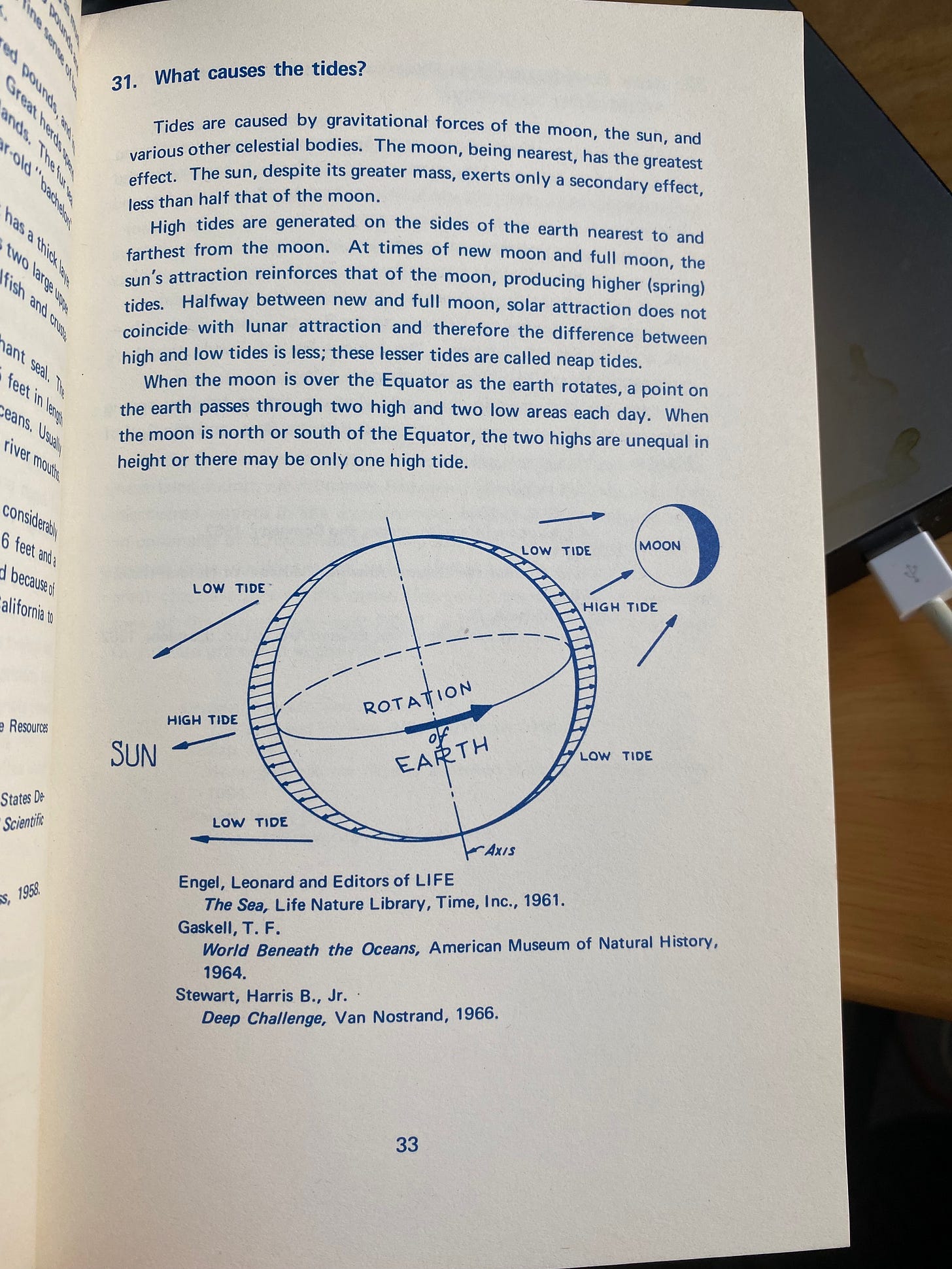

What causes the tides?

The first thing I thought of when I read this answer was planting with the signs and moon.

It is said that if you plant certain crops within certain astrological signs, your plants will thrive, while other signs are best for harvesting or planning. Each sign, in fact, has its correlate planting activity, no doubt based in part on the seasons of the northern hemisphere.

The moon is important here, too: Planting by the correct moon phase is said to have a profound impact on the crop's outcome. Aboveground crops (anything from which you harvest fruits, veggies, leaves) should be planted during the waxing moon, while root crops are said to do best planted when the moon is waning.

But it isn't just what we put in the ground, our folklore around the culinary cosmos connects with what we do with the produce once it's picked.

For example, I've heard from Appalachian elders that sauerkraut should only be made in a waxing moon, which allows the flavors in the food to grow as the moon does. Making sauerkraut with the waning moon is said to produce off flavors and a limp, unsatisfying final product.

I've not noticed a significant difference in my sauerkraut results based on moon phases, but I haven't intentionally timed it to match the phases before either. This little book on the oceans has inspired me to use my next few batches to do just that.

For some more deep dives into planting and preparing with the signs or lunar cycles, the Firefox books and the Old Farmer's Almanac are great starting points.

Some further questions:

We know that lunar gravity has real impacts here on earth, but do we know whether, or how, it impacts the growth of food crops or certain aspects of them? Does the water content in an apple, for example, rise or lower (even a tiny amount) with the proximity of the moon?

I would love to see a widespread study on how modern people describe the value of planting with the signs and moon. Purely in terms of yield/quality? Or is there something ephemeral or contextual: For example, carrying on tradition or connecting to ancestors?

What is Atlantis?

While I think that describing mythology as "history as seen through the eyes of the intellectually immature" is a bit...dismissive (to put it mildly), there are some other useful kernels in this answer, namely the acknowledgement that myth is not purely fiction: It is rooted within some amount of fact, whether that fact be the physical existence of a forgotten city, or the lived experience of people within a place.

Several years ago, The Wondersmith and I collaborated on an Atlantis-based project.In it, we both imagined what foods would have been eaten in Atlantis, but also brought some creative license to bear to create foods whose flavor and color were evocative of the mythical space.

The mead I brewed, for example, was a confluence of historical knowledge (using only herbs native to the Mediterranean for flavoring) and my desire to make a drink that tasted like the island itself (a process helped along considerably by my synesthesia).

The ultimate product was flavored with seaweed, Mediterranean herbs, and a touch of salt, and for some added oomph could be colored with pigment-packed flowers to look like seawater.

This question about the ocean has returned me to that particular creative headspace: What do we learn, for example, when we center food within our descriptions of these myths? What do we learn about the omission of food from such narratives? Where do the lines blur between the myth and the reality?

How many species of fish are there?

This is a seemingly straightforward question with a complex answer: In part, at least, because we can't assume to have identified every single creature living in the vast oceans of our planet.

But to me, it also speaks of transformation: Like the ecological succession mentioned above shifts our physical world, new information shapes our understanding of that world, impacting the metaphorical landscape of whatever disciplinary lens we apply.

This is a useful way to think about identifying fish.

But transformation is, it turns out, a really useful way to think about eating fish too.

Cooking is, in its essence, a transformative practice.

We can leave arguments around whether or how cutting up and eating a raw ingredient (like a carrot) falls on that spectrum, but most of the cooking we do is meant to transform, even if minimally.

But cooking doesn't always mean applying heat: To think of transformation, we need to move beyond the spectrum between "raw" and "cooked."

Cooking fish can include the way a sushi chef slices and serves a piece of sashimi: Making it a far cry from just a raw piece of fish on a plate.

In some cases (like sashimi) the transformation is near-instant: But transformation can also take time, even years, to complete.

Fish sauce is the epitome of slow food. It can take months, even years, to be ready, similar to the way soy sauce is often aged for a long, long time.

Like the ecological succession above, fish sauce represents transition happening on a small scale: Rich Shi and Jeremy Umansky note that it is largely an enzymatic rather than fermentative process, wherein salt and time meet the body (or bodies) of fish, shaping their transformative process.

As the body breaks itself down through its own digestive enzymes, it is preserved by the salt, becoming something new while still maintaining its component parts.

For fun, here is my fish sauce recipe from the Hidden Cosmos:

Fish sauce

The basic method for making fish sauce is to pack whole fish (guts included) in salt, then wait until a thin, umami-rich sauce develops and can be gently drained off.

You want to use a good amount of salt to fish to keep it from spoiling, and the fish sauce can take months or even years to develop the flavor you want: Most, however, seem to take about 12 months. If you want your sauce to develop more quickly, add koji: The ratios for koji fish sauce are in the book Koji Alchemy by Rich Shih and Jeremy Umansky.

Small fish (mackerel, smelt, sardine, etc.) work best, roughly chopped and packed in salt. I toss the fish with half the salt, then use the other half to layer on top of the salted fish as a cap to keep unwanted critters out.

1 lb fresh smelt, anchovy or other small fish, whole with guts

½ c sea salt

-Roughly chop your fish and toss with ¼ c of the salt.

-Pack your fish into a jar, pressing down to remove air pockets.

-Sprinkle the remaining ¼ c of salt evenly across the top of your fish.

-Set aside out of direct sunlight, and allow to process until a thin, dark sauce develops.

-Very carefully pour the sauce off your fish mixture into another container.

-The rest of the mixture can be strained and pressed to get a cloudy second pressing of fish sauce, if desired. You can also put the fish in a dehydrator, then grind when dry, to make an umami-rich seasoning salt.

* As a sidenote, NOAA had offices near my childhood home, and each year our high school would host an 'egg drop' off their building: Essentially creating different impact-proof containers for eggs, then chucking them off the building's roof to see which ones survived.